I went on a bit of a tear this year. I’m not sure why but I suspect that it’s at least partly related to reading a lot about writing, reading more chapter books with Idara, and also reading while I eat lunch.

Now that I’ve pasted in my notes from all of these books this post has ballooned to nearly 8,000 words, which is way too many, and I don’t expect anyone to read it all, or even most of it, so I’m not sure exactly what I’m doing here. That said, these posts have been well-received in the past, and I like keeping up the tradition, so here it is.

Next year I might do something different, like just list what I read and then go into more detail on my favorites. I’d like to make this more readable than a phone book.

Stars (★) mark the books that I liked the most. Please let me know if you have thoughts on any of them or recommendations for what I should read next. Here are the lists I posted in 2021, 2020, in 2019, and in 2018.

Contents

- Non-Fiction

- Zen in the Art of Writing

- ★ A Swim in the Pond in the Rain

- ★ Tightrope

- A Sand County Almanac

- In Love with the World

- DIY MFA

- ★ Yellow Bird

- Coming of Age in Samoa

- The Braindead Megaphone

- The Art of Character: Creating Memorable Characters for Fiction, Film, and TV

- How to Tell Stories to Children

- Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape

- ★ Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002)

- 24/6: The Power of Unplugging One Day a Week

- Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen

- Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

- The Porn Myth: Exposing the Reality Behind the Fantasy of Pornography

- Delivered: True Stories of Men and Women Who Turned from Porn to Purity

- The Miracle of Morning Pages

- The Shepherd’s Life

- ★ The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking

- Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

- Techniques of the Selling Writer

- The Pursuit of Perfection: And How It Harms Writers

- Man’s Search for Meaning

- Creating Short Fiction: The Classic Guide to Writing Short Fiction

- Writing Fiction: The Practical Guide

- Uncommon Sense Teaching: Practical Insights in Brain Science to Help Students Learn

- Consider This: Moments in My Writing Life after Which Everything Was Different

- Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organize Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential

- Fiction

- Tenth of December

- Of Mice and Men

- The Parable of the Sower

- Anton Chekov: Stories

- The Girl With All the Gifts

- A Good Man Is Hard to Find

- The Every

- ★ Slaughterhouse-Five

- Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine

- ★ Children of the New World

- ★ CivilWarLand in Bad Decline

- Tortilla Flat

- The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- The Perks of Being a Wallflower

- Winter in the Blood

- Homesick for Another World

- Chapter Books

- Favorite Picture Books

- Books I Gave Up On

Non-Fiction

Zen in the Art of Writing

by Ray Bradbury, finished January 12

Ray Bradbury is best known for Fahrenheit 451, which I read a few years ago and found underwhelming. It was an interesting concept that seemed to fall apart in the second half. This book, on the other hand, held my interest all the way through. A common theme: “Quantity gives experience. From experience alone can quality come.”

★ A Swim in the Pond in the Rain

by George Saunders, finished February 5

George Saunders, writer and teacher, is my hero. This book is as close as I’ll ever get to meeting him, and thankfully it gets me pretty darn close. This is a writers’ workshop in book form, with stories, commentary, and exercises.

One of the main themes is on revision, which he summarizes this way:

Who cares if the first draft is good? It doesn’t need to be good, it just needs to be, so you can revise it.

This idea shows up again and again in writing advice (Shitty First Drafts in Lamott’s Bird by Bird, for example), but I like Saunders’ spin on it, which is essentially to think about a meter flipping between positive feeling (good writing) and negative feeling (bad writing) as you reread a draft. Cut the parts that flip the meter into the negative and keep the parts that don’t.

★ Tightrope

by Nick Kristoff and Sheryl WuDunn, finished February 19

An intimate and heartbreaking look at what it means to be poor in today’s America, told through the eyes of Kristof, who “made it out” of poverty-stricken Yamhill, Oregon but kept in touch with many people who did not.

In a chapter which profiles a woman who spends time in prison for drugs, they write:

Individual offenders need to embrace the narrative of personal responsibility more fully, while American politics and society should be more skeptical of it.

In other words, we all need to see the ills of our nation as our own responsibility — whether collective or individual — rather than someone else’s.

The final chapter is filled with recommendations, many of which revolve around the idea of providing more “escalators” to help people get out of poverty, like well-paying blue collar jobs, better healthcare, etc. Here’s where they recommend focusing our attention:

- High-quality early childhood programs

- Universal high school graduation

- Universal health coverage

- Elimination of unwanted pregnancies

- A monthly child allowance

- An end to child homelessness

- Baby bonds to help build savings

- A right to work

One of the interesting things about the book is that it’s not a liberal polemic. It shows a tremendous amount of compassion for Trump voters, and includes plenty of conservative perspectives (personal responsibility first and foremost). Then again, it’s hard to ignore the fact that the Republican party have all but given up on offering up solutions to these problems. It seems the culture war is the only war they’re still willing to fight.

A Sand County Almanac

by Aldo Leopold, finished March 21

A Sand County Almanac is a book of place, like The Shepherd’s Life. It is centered around Leopold’s farm in Wisconsin.

The book is often mentioned alongside Silent Spring as books that kicked off the modern environmentalism movement. Having read Silent Spring last year I decided to read A Sand County Almanac this year.

I can see why the book has so much staying power. It might be summarized by the following sentences, quoted from early in the book:

Conservation is getting nowhere because it is incompatible with our Abrahamic concept of land. We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.

Another idea that sticks with me (and that I’ve seen elsewhere, possibly in Braiding Sweetgrass) is that if you think about it the right way, there’s no such thing as idle land:

There are idle spots on every farm, and every highway is bordered by an idle strip as long as it is; keep cow, plow, and mower out of these idle spots, and the full native flora, plus dozens of interesting stowaways from foreign parts, could be part of the normal environment of every citizen.

I can see myself returning to this book again in a few years, as I’m not sure you can get everything out of it on the first read through.

In Love with the World

by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche and Helen Tworkov, finished March 27

Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche snuck away from his monastery in order to take a “wandering retreat” and return to the roots of his beliefs. The book focuses mostly on self-denial and death. A portion of the book follows his time in a dirty train station where he sleeps on the floor, mostly, and occasionally springs for a cheap bed upstairs. He writes:

Without any training, I might have concluded that the railway station was the problem, not my mind. True, that station could have used some rat control, and had more efficient services for cleaning litter and poop. That would have been nice. But when we look at our middle-class lives, or at the lives of those who live vermin-free, with sufficient food and soft chairs, we do not encounter much contentment.

And so the book follows from those ancient ideas found in Buddhism, Stoicism, and elsewhere: that the world just is, and that happiness or suffering are a result of how we see it.

Later in the book, he becomes deathly ill after eating leftover food outside of a restaurant. This is the foundation for the other main theme in the book, death. He writes:

All things are impermanent. Death comes without warning. This body too will be a corpse.

He also compares drifting off to sleep as a kind of miniature death, a new idea for me:

Sleep is the most obvious of many daily deaths. Yet each micro-version of death can function as a portal through which we enter the realm of dying. Each experience of it allows us to learn about what we most dread; and to diminish our fears by befriending them.

The beginning of sleep represents the death of a day that I will never experience again. A kind of miniature death. And yet drifting off to sleep is one of the best parts of my day.

DIY MFA

by Gabriela Pereira, finished March 30

Gabriela Pereira wrote this book after completing her Master of Fine Arts (MFA) at The New School. Her conclusion was that she could’ve done a lot of the work herself and skipped the MFA. Having read the book, I ended up believing the opposite: that the feedback-oriented workshop simply can’t be replaced by a book about writing.

All of that said, there were plenty of parts that I liked. In particular, I liked the call to arms that comes at the conclusion:

Remember, too, that writing is a war of attrition. Many people want to write a book, but only a handful are able to stick with it long enough to see any progress. Writing is survival. You must stay on the battlefield after everyone else has given into defeat. “Overnight success” is a myth. The secret is to persist until everyone has given up and you’re the only one left standing.

★ Yellow Bird

by Sierra Crane Murdoch, finished April 2

An oil worker goes missing on an Indian reservation during the boom in North Dakota, and a Native woman makes it her personal crusade to find out what’s happened to him. Long, but incredibly captivating, plus an interesting look at modern life on Indian reservations and what happens to a community when they win the (natural resource) lottery.

Coming of Age in Samoa

by Margaret Mead, finished April 15

Mead presents anthropological research conducted in Samoa in the early 20th century, most of which focus on adolescence and sexual relations. It’s a fascinating, but also to be taken with an enormous grain of salt, since there’s apparently quite a bit of debate about whether her findings (especially those related to sexual promiscuity among youth) were correct.

The Braindead Megaphone

by George Saunders, finished April 29

This collection of essays, many previously published in GQ and The New Yorker covers everything from the idiocy of modern, mass media (“The Braindead Megaphone”) to Dubai (“The New Mecca”) to a Buddhist boy who was reported to have been meditating without food for six months by the time Saunders traveled to visit him in Nepal (“Buddha Boy”). Saunders can do no wrong in my mind, so take my endorsement with a grain of salt, but I loved this book, too.

A few favorites:

- “The New Mecca” (brought back lots of memories of my time in Qatar)

- “A Brief Study of the British” (reminded me of Bill Bryson)

- “Mr. Vonnegut in Sumatra” (a kind of personal history about his origins as a writer)

- “The Perfect Gerbil: Reading Barthelme’s ‘The School’” (Even if this book of essays had been terrible, which it’s not, it would’ve been worth it to have been exposed to “The School” which is one of the funniest things I’ve ever read.)

The Art of Character: Creating Memorable Characters for Fiction, Film, and TV

by David Corbett, finished May 25

This was a long and exceptionally detailed guide on figuring out who your characters are and why they do what they do. I skimmed parts of it because I knew that Corbett was giving me more than I could possibly take in. But the common theme that unified the book (or at least my read of it) was still useful: figure out why a character does what they do and everything else will fall into place.

And here’s a good reminder for me, someone who finds it much more natural to describe thought and feeling than words and action:

Characters reveal themselves more vividly in what they do and say than in what they think and feel.

How to Tell Stories to Children

by Joseph Sarosy and Silke Rose West, finished July 12

Idara and Oren love having stories read to them, but an even better treat is to have a story told to them. It takes a tremendous amount of energy, especially after a long day of work, and so it’s not something I do often. When I do it feels good. Like I’ve given something of myself to them that they recognize as especially valuable. The authors describe it like this:

When a child says, “Tell me a story!” she is not asking for a narrative. She is asking for your attention.

The general guidance of the book is summed up in what they call the storytelling loop: “…a real situation, followed by imaginary development, that results in a new reality….” So for example, let’s say on the way home we saw a baby blue Volkswagen Beetle. That’s the real situation. The imaginary development might be that it’s actually being driven by a whale who’s taken a wrong turn out of the ocean and ended up on dry land. And now the new reality is that whenever we see a baby blue car we try to spot the whale inside.

Islands of Abandonment: Nature Rebounding in the Post-Human Landscape

by Cal Flyn, finished July 21

What happens to the land when people leave it alone? This is one of the most interesting questions in the world to me, and so when I found it at the Paulina Springs Bookstore in Sisters, Oregon it felt as if Flyn had written it specifically for me (if so, thank you!). I wish I’d taken more careful notes while I was reading it, but this is a short list of what sticks out to me five months after I finished it.

- Thanks to urbanization and high intensity farming, land is being abandoned by humans and returned to “nature” at a record-breaking pace.

- By and large, when people leave a certain area it returns quite quickly to what we consider a “natural” state (coyotes on the Golden Gate Bridge during the pandemic lockdown, for example).

- I put quotes around natural above because once humans have occupied a place (whether by grazing sheep or clearing with fire or mining uranium) it will essentially never return to the state it was in before humans arrived.

- The toxicity of dioxins is mind-boggling. Say there’s a crab in an area contaminated with dioxins. It can survive, at least until you fish it out and eat it. The problem for you is that single crab contained enough dioxins to give you cancer.

- Cattle are extremely social animals, as shown by the author’s excursion to an island where they’ve lived undisturbed by humans for generations. This had me thinking about the beef and dairy industry, and what it must feel like for cow and calf to be separated in the interest of producing milk for human consumption.

★ Theft by Finding: Diaries (1977–2002)

by David Sedaris, finished August 22

Of all the books I read this year, this one might have brought me the most joy. I bought it on a whim at a little bookstore in Manzanita (Cloud and Leaf, I think) and was a hundred pages in before I’d even realized it. Sedaris is a total weirdo and there’s no better way to witness that than through his diaries.

24/6: The Power of Unplugging One Day a Week

by Tiffany Shlain, finished August 30

Take the traditional Jewish sabbath, a period of rest from sundown on Friday till sundown on Saturday, and apply it specifically to the digital technology of the 21st century, and you have the general thesis of this book. The method Shlain employs with her family (husband and a couple kids, if I remember correctly) is centered around putting away laptops, tablets, and smartphones. They keep a landline for emergencies and to keep in touch with extended family.

It takes some preperation. For example, she keeps a landline in case of emergency, and prints out directions the day before to avoid having to rely on navigation apps. I tried this for about a month, but found that simply not checking email or the news or reddit for a day was all I needed in order to reorient myself away from the digital world. This still made space for video calls with family, which is how we usually spend Saturday mornings.

Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen

by Dan Heath, finished September 10

I read Chip and Dan Heath’s Made to Stick about 15 years ago and still remember the core thesis of the book (for an idea to be memorable it must be simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional, and told via stories). This book isn’t nearly as memorable or helpful, but it did provide some interesting examples of people trying to solve problems before they occur.

Save the Cat! Writes a Novel

by Jessica Brody, finished September 18

Breaks down novels (and a few movies) into a fifteen parts spread over three acts. If I wanted to write a novel right now this is the method and structure I’d follow.

The Porn Myth: Exposing the Reality Behind the Fantasy of Pornography

by Matt Fradd, finished September 24

Over the summer I had a conversation with a friend about how unprepared we were to be adolescent boys with high-speed internet access. Our parents were unprepared, too. Now that I have kids of my own and work with young people I thought that I should know read more about pornography, something which is at once ubiquitous and invisible.

Matt Fradd is a religious writer and the book is essentially an anti-pornography polemic (as one might guess from the title). He writes about the effects porn has on the consumer as well as on the producers.

Sometimes people criticize certain books saying that they could’ve been a blog post. This is one of those books. I think the anti-pornography case is made much better in “The Naked People on Your iPod,” though sometimes it’s important to read a book if only to spend a few hours thinking about one thing.

Delivered: True Stories of Men and Women Who Turned from Porn to Purity

by Matt Fradd, finished September 25

There’s no question that porn ruins some people’s lives, but it seemed like most of the ruin described in this book was not because of porn but because the people profiled created a perfect image of purity in their head and were (of course) unable to achieve it.

The Miracle of Morning Pages

by Julia Cameron, finished October 1

On the first day that I tried Morning Pages, I wrote in my notebook: “Tried it today, October 2, 2022. Took me about 45 minutes to write the three pages. Not sure if my wrist can handle three pages of writing every day.”

Since then I’ve made it a regular habit. I wake up before everyone else, make tea, and start writing. I did three pages for a couple months and then decided to switch to two so that I’d have more time for other writing projects. I usually skip one day a week so I can wake up with Rachael. The habit totally falls apart when I travel. My wrist is fine.

The Shepherd’s Life

by James Rebanks, finished October 21

A collection of autobiographical sketches from a man whose family raises sheep in England. I enjoyed it. Reminded me a bit of H is for Hawk.

★ The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking

by Oliver Burkeman, finished October 23

When we returned to Baku in August I fell into a kind of light depression, if there is such a thing. I wanted to be somewhere else, to be doing something else. This book came along at precisely the right time and reminded me of all the ideas that had helped me manage sadness in the past, like Stoicism and meditating on death (and how magical it is that we have the opportunity to live). I cannot recommend it enough.

Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

by Robin Wall Kimmerer, finished November 10

I happened to read this during a trip to Sim, Azerbaijan, which is one of the greenest and wettest places I’ve ever visited (you can see some pictures here). As you might expect, nearly every surface was covered in moss. And not just a thin coating — in some places the moss covered rocks and trees like a down blanket.

Anyway, the book is fascinating, and I highly recommend it, especially if you have any interest in science or enjoyed her other book, Braiding Sweetgrass. One interesting thing I learned from the book is this:

Raw rock is inhospitable to mosses. The surface must first be weathered by wind and water, and then etched by the acids produced by a lichen crust.

A random rock I photographed in Sim, Azerbaijan.

A random rock I photographed in Sim, Azerbaijan.

Techniques of the Selling Writer

by Dwight Swain, finished November 20

Another dated writing book but with valuable and unique advice. One idea that stands out is before focusing on plot or character, to pay attention to your own feeling so that you may better arouse it in someone else. He writes, “If you haven’t got a feeling, you can’t write about it, let alone arouse it in somebody else.”

The Pursuit of Perfection: And How It Harms Writers

by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, finished November 22

There are two parts to this, one of them is about writing workshops and perfectionism and the other one about marketing. I found the first part more interesting than the second, probably because I read it while I was participating in a writers workshop. The basic idea is that in many writers workshops the submissions are torn to pieces even when they’re works in progress from beginning writers. Much better, Rusch argues, to find ways to encourage so that they’ll keep writing. I’m trying to channel this advice in my own feedback.

Man’s Search for Meaning

by Viktor Frankl, finished November 27

It’s interesting to me how so many parts of religion and philosophy come back to the idea that all we can really choose is how we respond to the world around us. Frankl describes it this way:

…everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. (p. 66)

I read this for the first time on a trip to the Dominican Republic when I was in college. I can still remember sitting in a damp and poorly-lit university hallway turning the pages. Unfortunately I didn’t remember much about the content of the book, so I decided to read it again. In addition to the main theme about suffering bravely and deriving meaning from that suffering, one part that stuck out to me was about how realities in the past are better than possibilities in the future. Nothing can ever take those away. Which relates, in a not-so-roundabout kind of way, to some interesting ideas about Einstein’s theory of relativity. Frankl writes:

It is true that the old have no opportunities, no possibilities in the future. But they have more than that. Instead of possibilities in the future, they have realities in the past — the potentialities they have actualized, the meanings they have fulfilled, the values they have realized — and nothing and nobody can ever remove these assets from the past. (p. 151)

One way I comfort myself against the fear of some horrible event in the future is to remind myself that the wonderful things I’ve experienced in the past (my childhood, meeting Rachael, being a father to Oren and Idara) can never be taken away from me. Of course, Frankl describes it much better than I ever could.

Creating Short Fiction: The Classic Guide to Writing Short Fiction

by Damon Knight, finished November 28

So many great parts in this, despite the fact that it was published over 40 years ago and felt a bit dated in parts (particularly with regards to the publishing industry — but what do I know?). Knight was cofounder of the Clarion Writer’s Workshop, and grew up in Oregon.

I saw a review which compared it to On Writing by Stephen King and The Elements of Style and I think that it’s in that ballpark, in terms of quality and helpfulness. The only thing that I was left wanting more of was advice oriented toward short story writing. This book is more about fiction in general, despite the title.

Writing Fiction: The Practical Guide

by Alexander Steele and Peter Selgin, finished December 9

Based on the Fiction I class at the Gotham Writer’s Workshop, this book is essentially an introductory writing workshop in book form. Each chapter in the book mirrors a week of reading and exercise in the class.

It’s not bad. It organizes the topics in a helpful way, covering character, plot, point of view, description, dialogue, setting and pacing, voice, theme, revision, and business.

Uncommon Sense Teaching: Practical Insights in Brain Science to Help Students Learn

by Barbara Oakley, Beth Rogowsky, and Terrence J. Sejnowski, finished December 21

One of the books that helped me get back on track as a student was Barbara Oakley’s A Mind for Numbers, so I was excited to see this book pop up on a recommendations list. It’s a good review of best practices in teaching, along with a great discussion of the value of direct instruction versus exploration. Essentially, direct instruction is more valuable with older students and more cognitively demanding tasks (sometimes described as “biologically secondary”), while exploration is more valuable for younger students learning things that are less demanding (like language, which is considered “biologically primary” because nearly all children learn it on their own without being explicitly taught).

There’s also a great section on the brain’s declarative system (which is engaged when someone is explaining how to use a clutch, for example) versus the procedural system (which is engaged once you’re practicing driving a manual on your own). The systems are not in conflict – most skills start in the declarative stage (someone shows you) and then move to the procedural stage (you practice so much that you can do the thing without thinking).

Generally, textbook chapters convey declarative knowledge. The problems at the end of the chapters, on the other hand, are meant to also invoke the procedural system. Both explanations and problems are essential in helping a student master the material.

There’s also an insightful discussion of stress later in the book.

A common belief is that stress is always bad—that it leaves students paralyzed or in a frenzy. But the uncommon sense teacher knows that moderate stress can be your and your students’ friend.

My students often talk about being stressed out and how they want to minimize stress at all times, but to learn is to grow, and we cannot grow without being under some degree of stress.

Consider This: Moments in My Writing Life after Which Everything Was Different

by Chuck Palahniuk, finished December 22

Part autobiography, part writing advice. Not unlike Stephen King’s On Writing. I think I actually liked this book more. Aside from a few short stories (like the short story “Guts,” which I read when I was in high school), I’d never read anything by Palahniuk. I remember that story being disgusting, but also captivating, so I don’t know why I haven’t read more of his stuff. Maybe I will.

Anyway, my two favorite ideas of the book are about clocks, guns, and voice. A clock, according to Palahniuk, is a device added to a story to enforce a conclusion on a particular timeline. For example, in Titanic, the ship starts sinking and we know that the story must resolve (more or less) by the time it goes under. Or in The Martian, Mark Watney will soon run out of food. The clock is ticking, which raises the tension of the story.

If your stories tend to amble along, lose momentum, and fizzle out, I’d ask you, “What’s your clock?” And, “Where’s your gun?”

The other idea is about what Palahniuk calls “big voice” and “little voice,” which is similar to the directive: “show, don’t tell.”

Little voice gives us the facts. Big voice gives us the meaning—or at least a character’s subjective interpretation of the events.

I rely too much on “big voice” in my writing and am trying to change that.

Building a Second Brain: A Proven Method to Organize Your Digital Life and Unlock Your Creative Potential

by Tiago Forte, finished December 25

Basically: Write stuff down. Be organized about it. Organize your notes by project. But don’t aim for perfection. A collection of notes is a working document and takes its value from being added to, updated, and changed.

This is perhaps the most important part of creative work, which Forte encapsulates as follows:

Sebastian Junger once wrote on the subject of “writer’s block”: “It’s not that I’m blocked. It’s that I don’t have enough research to write with power and knowledge about that topic. It always means, not that I can’t find the right words, [but rather] that I don’t have the ammunition.”

Later in the book he writes:

What I learned from my father is that by the time you sit down to make progress on something, all the work to gather and organize the source material needs to already be done.

Although the book was just okay, I loved this part. It’s another angle on the idea that one should write what they know. You have to learn about something to write about it, and if you don’t write that knowledge down you won’t have anything to go off of.

Fiction

Tenth of December

by George Saunders, finished January 7

A collection of short stories by George Saunders. My favorites were:

- “Sticks”

- “Escape from Spiderhead”

- “The Semplica Girl Diaries”

- “Tenth of December”

Of Mice and Men

by John Steinbeck, finished January 10

One of my favorite books when I was younger was East of Eden. I still admire Steinbeck’s efficient use of language and his description of a scene. This book, I learned from the introduction, was written as much as a play as it was a novel. It’s easy to see how each of the parts of the book (George and Lennie down by the river at the beginning, arriving at the ranch, etc.) maps neatly to the scene of a play.

In the introduction, Susan Shillinglaw quotes Steinbeck: “Knowing a man well never leads to hate and nearly always leads to love.” She goes on to point out that Steinbeck and his friend Ed Rickets “emphasized the need to see as clearly as a scientist: that is, to accept life on its own terms.” These were not competing ideas, and they come together beautifully in this book.

There are lots of things I love about this book, so it’s hard to choose just one. The thing that stands out, though, is its clarity. I suppose it doesn’t leave the reader much to uncover or chew on, clear as it is, but I think that the underlying meditation on how people with power treat those without (whether mice, or old dogs, or mentally disabled people) is plenty for any book to take on.

The Parable of the Sower

by Octavia Butler, finished March 8

I loved the near-future post-apocolyptic world created by Butler, but found that the story dragged once they set out on the road.

Anton Chekov: Stories

by Anton Chekov, finished (most of them) April 18

I didn’t read every story in this but my favorites were:

- “At Christmastime”

- “The Huntsman”

- “The Lady with the Little Dog”

- “A Boring Story”

I’ll come back to these stories again.

The Girl With All the Gifts

by M. R. Carey, finished May 3

This had one of the best openings of a novel I can remember reading, but then it became a little more predictable. Worth reading the first few chapters, though, even if you don’t end up reading the entire book.

A Good Man Is Hard to Find

by Flannery O’Conner, finished June 14

A collection of short stories by the Southern Gothic writer Flannery O’Conner. The one that sticks out the most to me (writing this in December) is the title story, which is about a traveling family and a serial killer.

I also remember a story entitled “The Artificial Nigger,” about a white boy and his grandfather traveling to Atlanta for the first time and getting lost in the city. The story takes its name from a plaster statue of a black man with a watermelon in a wealthy suburb.

The Every

by Dave Eggers, finished July 10

Jane recommended The Circle back when I was studying computer science and applying for internships at Amazon and big tech companies (hard to believe that this was something I was once pursuing). I never got around to reading it, but I loved Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius and listened to an interview with him on the Bookworm podcast from KCRW (which I originally heard about from Mason Currey’s Subtle Maneuvers).

Anyway, The Every is a kind of dystopian sequel to The Circle. It’s not particularly insightful, but it’s mockery of the company at the center of the book (which is essentially a fictionalized Amazon) was fun to read.

★ Slaughterhouse-Five

by Kurt Vonnegut, finished August 4

One of my favorite novels from this year. My favorite part was the fictionalization of one of the most fascinating theories in physics: that your future is not only predetermined, it already exists. More on that here.

All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist.

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine

by Gail Honeyman, finished August 6

Vanessa and I agreed to read each other’s book recommendations while we were camping last summer. I recommended Eating Animals and she recommended this. Finished it during our trip from Portland back to Baku. It wasn’t bad.

★ Children of the New World

by Alexander Weinstein, finished September 2

I happened upon a signed copy of this book at Paulina Springs Bookstore in Sisters, Oregon. I didn’t have high expectations since I found it in the bargain bin, but I ended up really enjoying it. The title story, about a couple who have children in virtual reality and then have to reboot their server (thus “killing” the children) was one of the most moving stories I read all year.

★ CivilWarLand in Bad Decline

by George Saunders, finished September 13

There were so many great stories in here that it’s hard to choose a favorite. The ones I liked the most were:

- “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline” (about a near-future Civil War-themed amusement park)

- “Isabelle” (about bad cop and the love he shows his handicapped daughter)

- “The 400-Pound CEO” (about the truth about a humane pest removal service)

- “Destitute Mary’s Failed Campaign of Terror” (about an old woman sabotaging her former place of employment)

Tortilla Flat

by John Steinbeck, finished September 20

This was Steinbeck’s first commercial success. I don’t think Steinbeck could’ve published this today, a white man writing a book about a bunch of homeless drunkards with brown skin who spend their entire day trying to figure out how to get their next gallon of wine. Even so, the book is filled with humanity, especially for a character who’s simply referred to as ‘The Pirate.’ Reminded me of “Cannery Row” but not as funny.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

by Mark Twain, finished October 12

I’m sure I was assigned this in school but this was the first time I’ve ever read it. It felt a bit drawn out, especially at the end, but interesting to see how modern a book it is, especially given that it’s over 120 years old. The whole ‘we didn’t actually have to break him out’ part about Jim was a bit of a letdown, especially since Twain harped on Tom’s plans for breaking him out for so many pages. Especially enjoyed the parts with the Duke and the King.

The Perks of Being a Wallflower

by Stephen Chbosky, finished October 21

I felt like I was reading a book about my own life. Not that I had the maturity or insight that Charlie possesses, but I definitely worried a lot, and worried about many of the same things. I really enjoyed this.

Winter in the Blood

by James Welch, finished October 31

I learned that this is a Native American classic after I finished reading it. It’s short and follows a nontraditional story structure. It reminded me a bit of The Odyssey because of its meandering nature.

Homesick for Another World

by Otessa Moshfegh, finished December 28

Weird and interesting. Favorite stories were “Bettering Myself,” “Mr. Wu,” and “Nothing Ever Happens Here.” I also read an essay by Moshfegh entitled “How to Shit” (which is actually about writing, not defecation). In it, she writes:

[Conventional narrative] is very reasonable. It’s also very limited. In my writing, I like to use the mainstream paradigm and fuck with it to point out its limitations.

It explains a lot of the stories in this collection.

Chapter Books

My Side of the Mountain

by Jean Craighead George, finished January 10

I read this book when I was young. Was I seven or seventeen? I can’t remember. What I do remember is that I loved it. And I loved reading it to Idara, too.

★ Hatchet

by Gary Paulson, finished February 4

Like My Side of the Mountain, I read this when I was younger and read it to Idara at bedtime and when we rode the bus to school. This book is quite a bit more grown up. It includes divorce and death, for example, which I mostly skipped over.

★ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe

by C. S. Lewis, finished February 19

As soon as Idara and I finished this she asked to read it again, so we did.

The Boxcar Children: The Lighthouse Mystery

by Gertrude Chandler Warner, finished March 22

Read this with Idara. It’s idealized and not very interesting, but Idara loved it.

The Flight of the Phoenix

by R. L. LaFevers, finished April 22

Another middle grade book that I read aloud to Idara. It was okay.

The Worst Witch

by Jill Murphey, finished May 2

A middle grade book about a girl who goes to a school for witches. Similar in plot to Harry Potter, and interesting to read because of how much more rich the Harry Potter universe is in comparison.

James and the Giant Peach

by Roald Dahl, finished June 13

This was the first children’s book written by Dahl (he also wrote a lot of adult fiction). It was also the first book by him that Idara and I read together. It was fun creating voices for the different characters, though I’m sure it drove everyone else on the bus nuts.

★ Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

by J.K. Rowling, finished November 4

Idara and I started this last year but didn’t finish. I think she lost track of the plot and so lost interest in the book. This time she was constantly reminding me where we were in the book and asking to read it at every opportunity. And like the first one, it’s fantastic.

The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip

by George Saunders, finished November 10

Read this over a few sittings on the couch with Oren and Idara. It was sort of half-chapter book, half children’s book. Reminded me of Roald Dahl. Not my children’s book from this year.

Because of Winn-Dixie

by Kate DiCamillo, finished November 29

Read this one with Idara. It was cute. I particularly liked the little story about Littmus Lozenges, an old candy that featured sorrow as a key ingredient. When different people in the story try the lozenges they remind them of different things in their lives which have made them sad.

Favorite Picture Books

Here are a few of our favorite picture books we read this year.

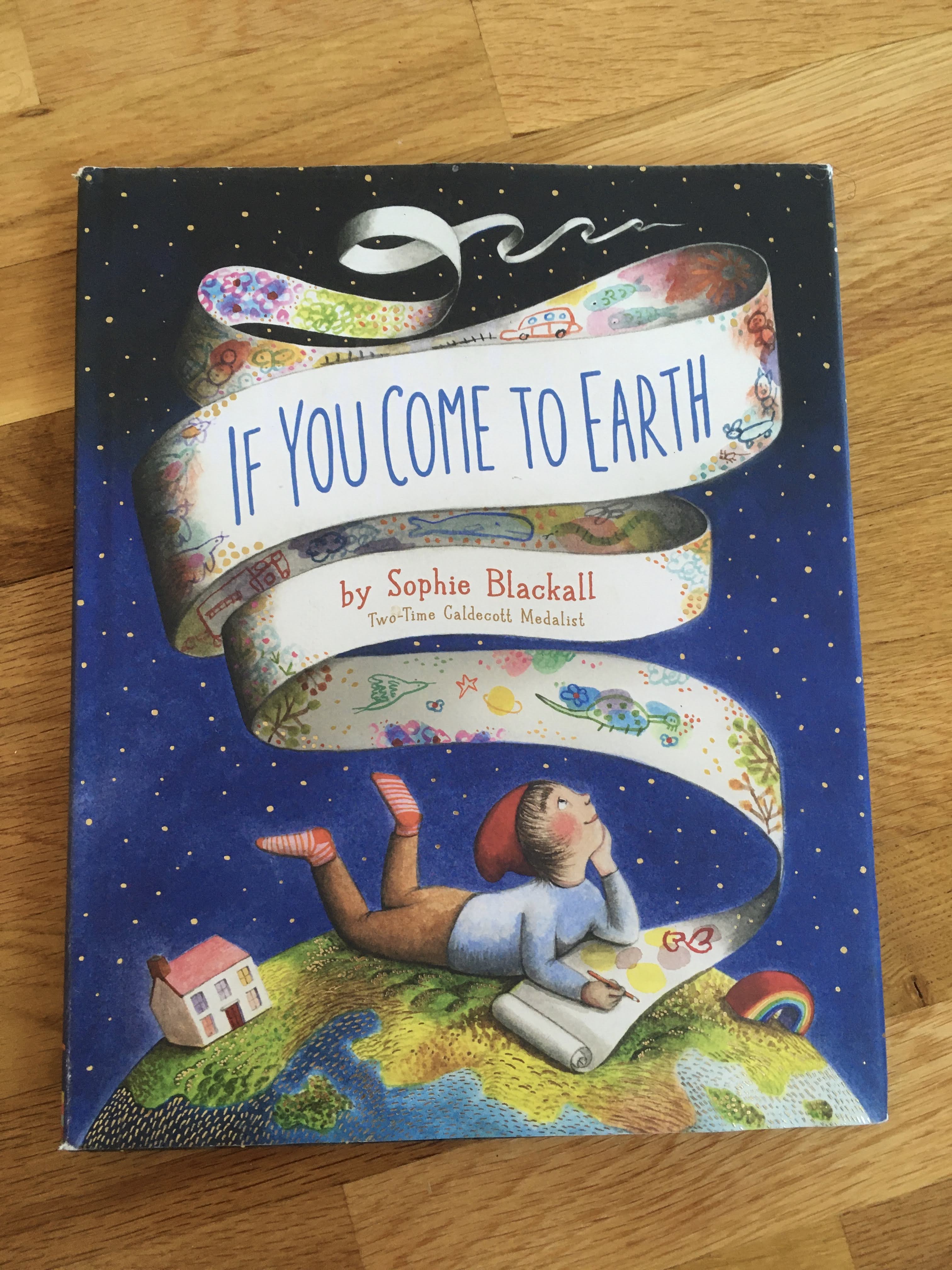

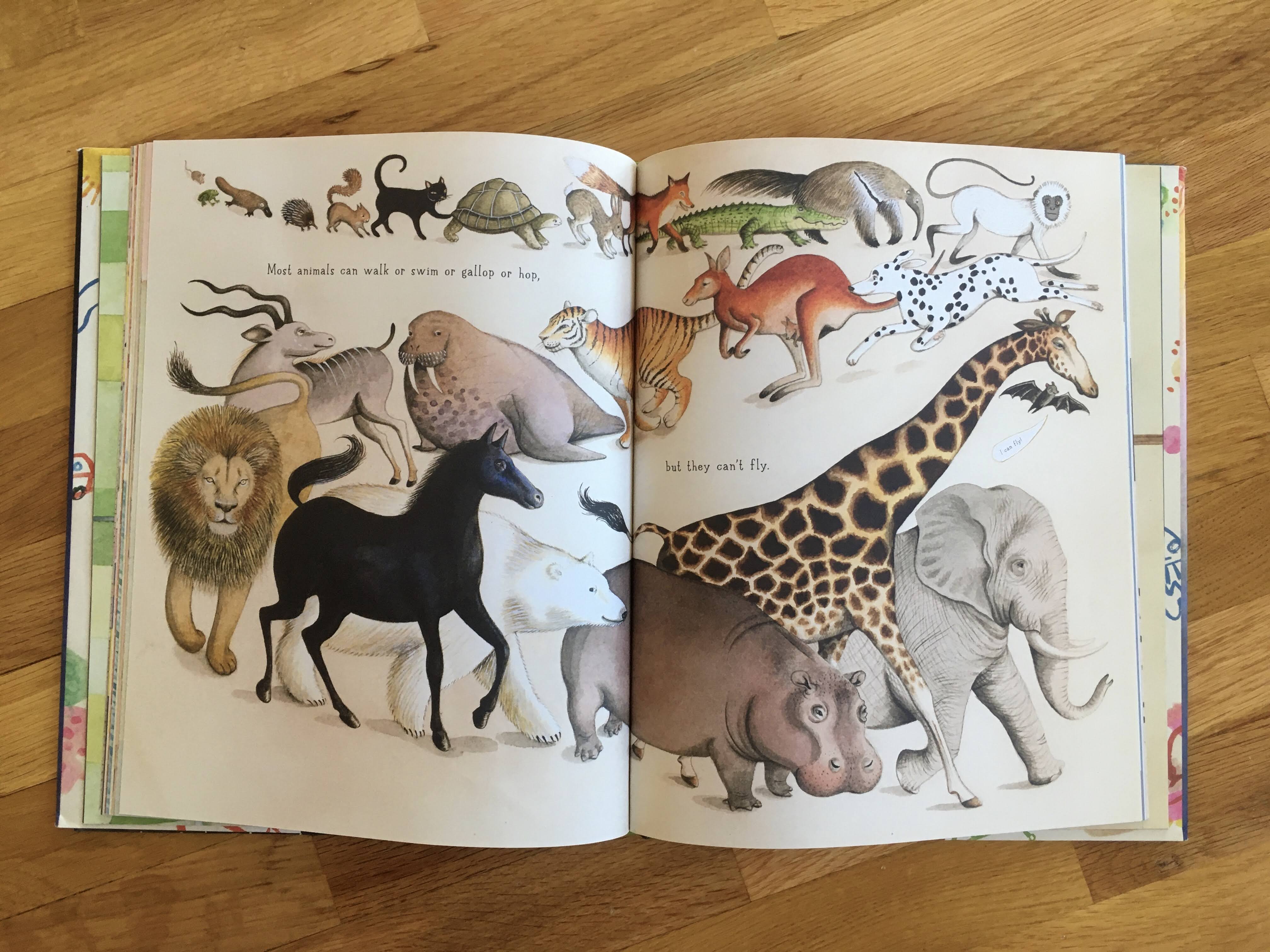

If You Come to Earth

Sophie Blackall

How would you explain earth to an alien? Where people live? What people eat? How people treat each other? This book tries, and doesn’t sugarcoat, either. Blackall talks about fighting and war and homelessness, but all in language and imagery that’s appropriate for kids.

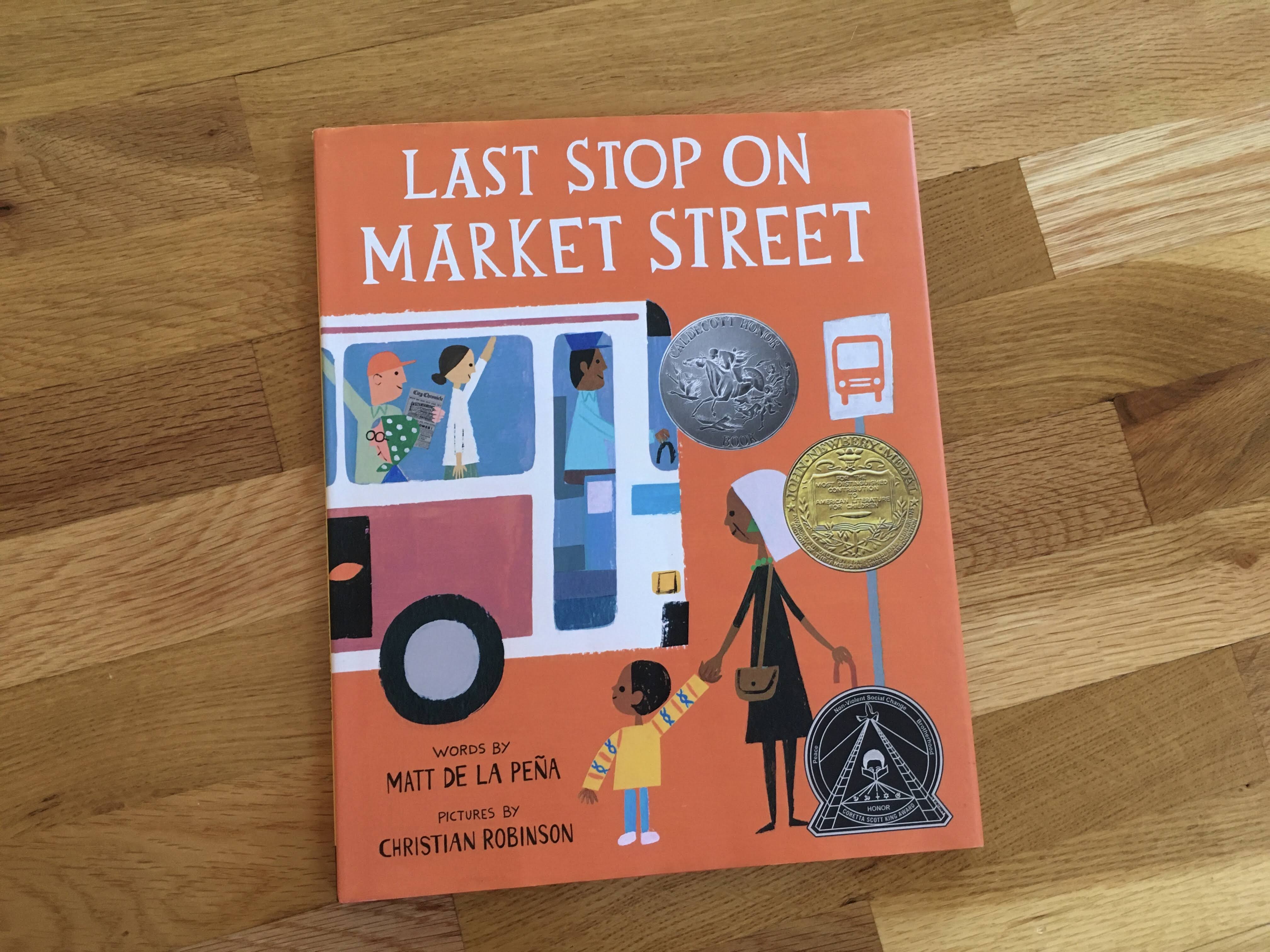

The Last Stop on Market Street

by Matt de La Peña and Cristian Robinson

It’s a simple story about a boy and his grandmother taking the bus from church to the soup kitchen, but it’s a rich story, too. It won the Newberry Medal, which apparently is very rare for picture books.

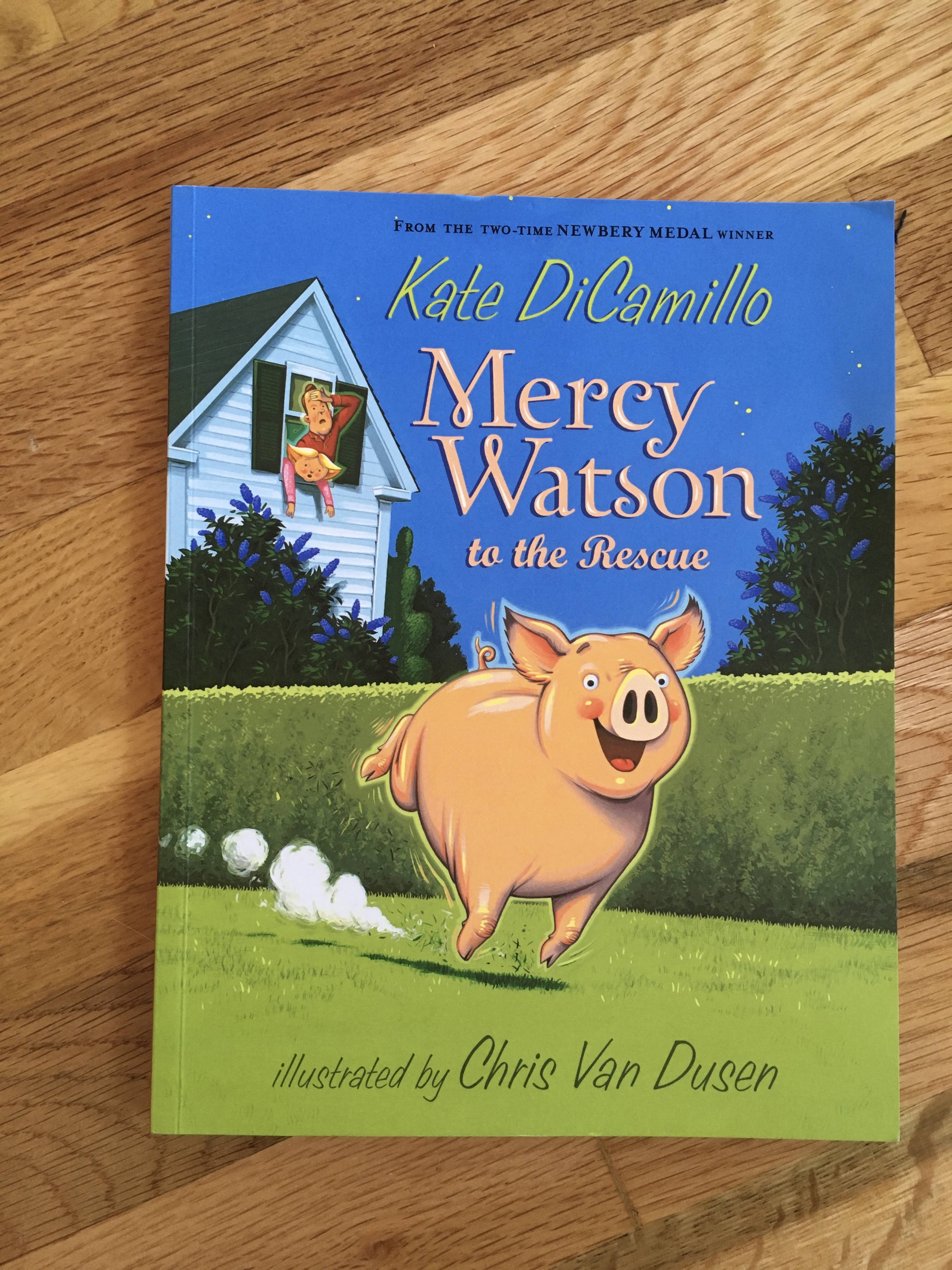

Mercy Watson to the Rescue

by Kate DiCamillo

By the same author as Because of Winn-Dixie. The setup is that there’s a suburban couple who have pet pig that they treat like the perfect child. But the pig just wants to eat.

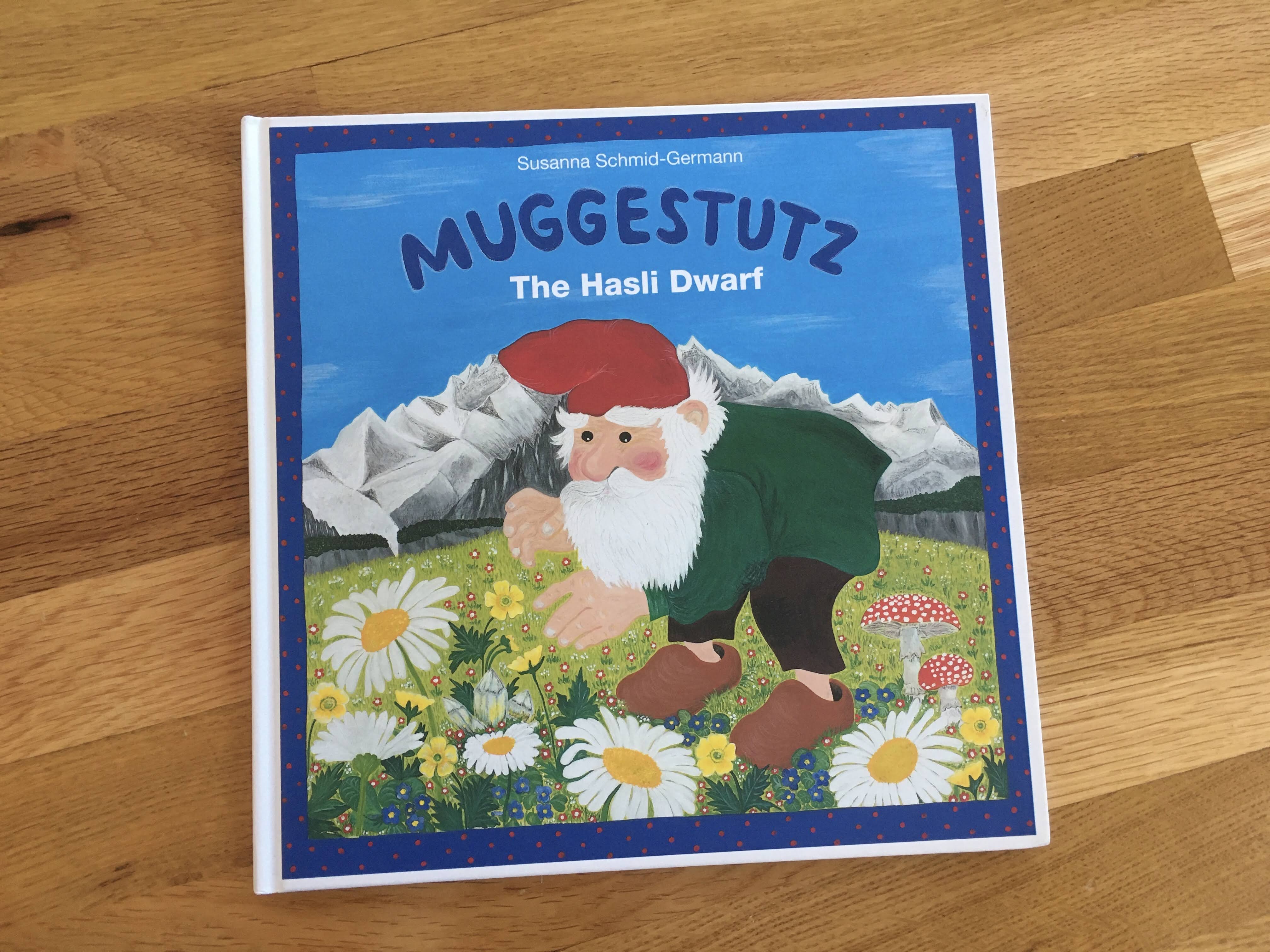

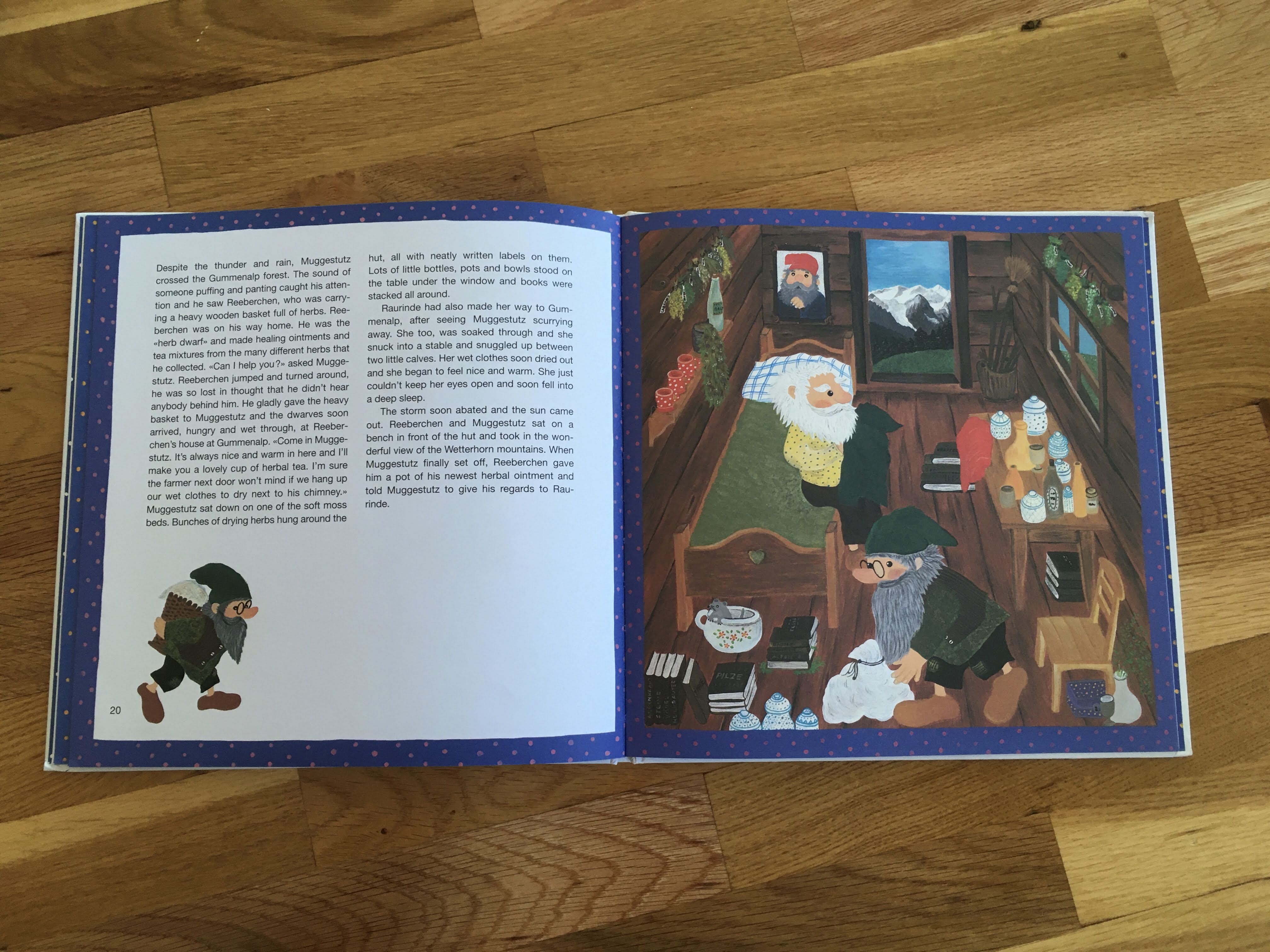

Muggestutz: The Hasli Dwarf

by Susanna Schmid-Germann

When we were in Switzerland with my sister’s family this summer we happened upon the Hasliberg Hike, a walk through the woods that follows a story about a dwarf named Muggestutz. There are stations along the way with things that bring the story to life, like play cottages that are so realistic they look as if the dwarf who lived there stepped out just before you arrived. This book follows the story of Muggestutz and his journey.

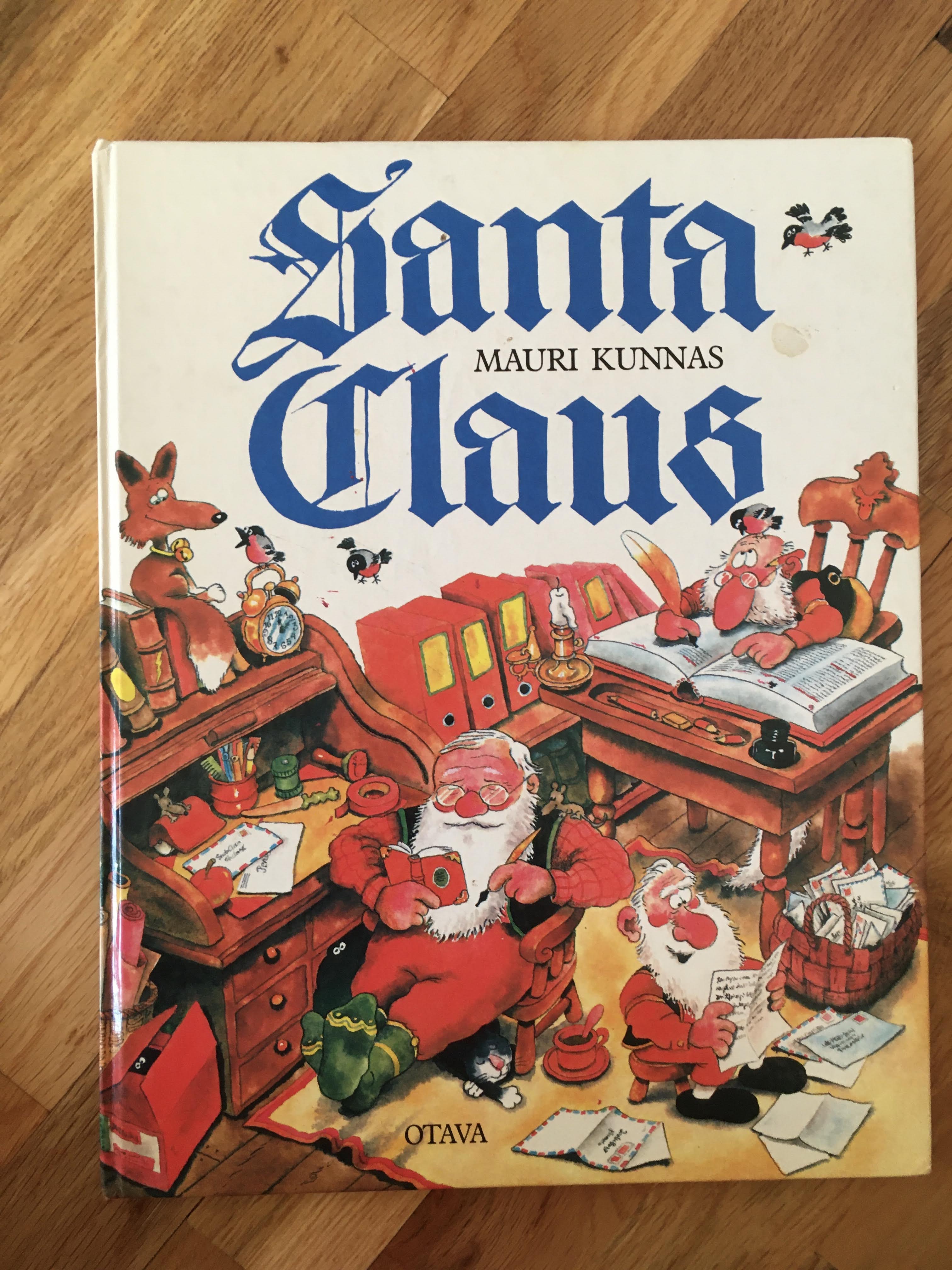

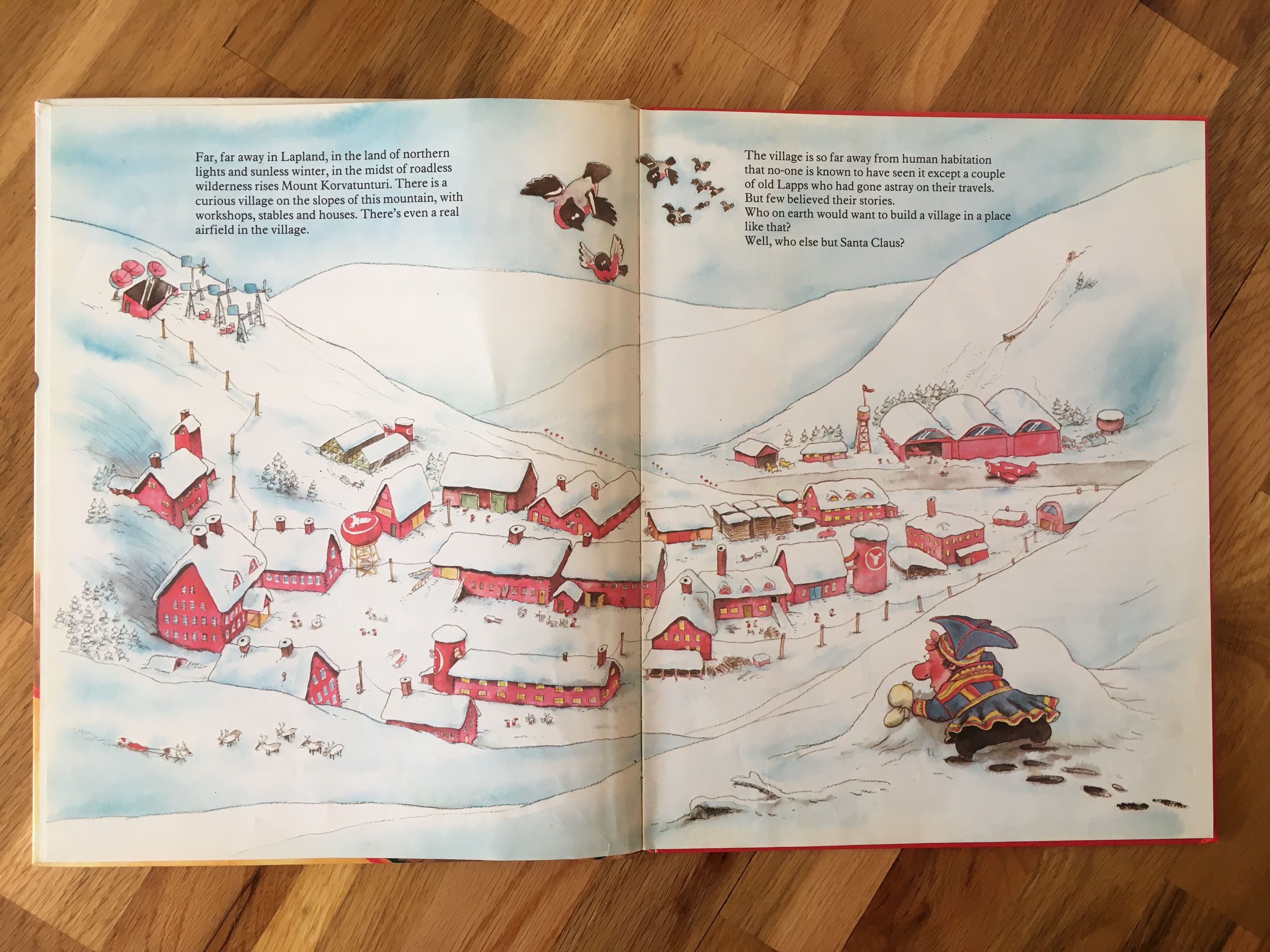

Santa Claus

by Mauri Kunnas

When I was little we had an exchange student from Finland named Ingrid who gave us this book as a gift. It sat on our coffee table for years during Christmas and then disappeared. I recently rediscovered it in a box and so read it to Oren and Idara half a dozen times reading up to Christmas. It’s a bit like a Richard Scarry book, but instead of Busytown it talks about what life is really like in Santa’s Christmas village.

Yertle the Turtle

by Dr. Suess

I found this at a bookstore in Baku. Like many Suess books, it’s particularly fun to read aloud.

Books I Gave Up On

No One Belongs Here More than You

by Miranda July, gave up after a couple of stories

This book of short stories felt like it was trying hard to be unique but that the uniqueness wasn’t paying off in terms of comedy or insight or general entertainment. The stories were certainly unique (there’s one about a woman teaching a swim class for elderly people in her apartment), but so is orange juice on cereal.

The Fifth Season

by N.K. Jemisin, gave up at about ten percent

I try science fiction and fantasy from time to time but I just can’t get into it. World building is interesting to me as a concept (World Building on Stack Exchange makes for great procrastination reading), but often when I read through someone’s creation I can’t help but find it tiring. I made it about ten percent of the way into this book before deciding to read something else.

No Time to Spare

by Ursula K. Le Guin, got about a third of the way through

Every year I try a new Le Guin book and each year I give up on it. Please don’t judge me.

A Time of Gifts: On Foot to Constantinople — From the Hook of Holland to the Middle Danube

by Patrick Leigh Fermor, got about fifteen percent through

This was great in miniature but hard to stomach page after page. I just couldn’t tell if we were getting anywhere or if anything particularly interesting was going to happen.