This year I set out to read about one book per week. I came close to meeting my goal, but then toward the end of September things fell apart (check out my other posts for an idea why). I’m back at it, though, and hope to continue the trend next year. At least for me, there’s hardly a more rewarding leisure activity than reading a book.

Stars (★) mark the books that I liked the most. Please let me know if any of these resonated with you, too, or if you have recommendations for what to read next.

Contents

- Non-Fiction

- ★ How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

- The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

- ★ When Breath Becomes Air

- Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

- ★ Blankets

- Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades

- The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics

- ★ The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters

- The Communist Manifesto

- ★ Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

- Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results

- Rejection Proof: How I Beat Fear and Became Invincible

- When Strangers Meet: How People You Don’t Know Can Transform You

- ★ Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

- This Is Marketing: This is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn To See

- TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

- The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure

- Do You Talk Funny?: Seven Comedy Habits to Become a Better (and Funnier) Public Speaker

- Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

- The Mueller Report: Executive Summary

- The Art of Community: Seven Principles for Belonging

- Birth Partner: A Complete Guide to Childbirth for Dads, Doulas, and Other Labor Companions

- Sweet Dreams, Story Catcher

- Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams: Explorations in Massively Parallel Microworlds

- Nix the Tricks: A Guide to Avoiding Shortcuts That Cut Out Math Concept Development

- Markings

- Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think

- ★ The Unsettlers: In Search of the Good Life in Today’s America

- Dive Into Inquiry: Amplify Learning and Empower Student Voice

- ★ Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace

- The World Without Us

- The Tao Te Ching

- Keep Going

- The Life You Can Save

- Fiction

- Poetry

- Children’s Books

Non-Fiction

★ How to Invent Everything: A Survival Guide for the Stranded Time Traveler

by Ryan North, finished January 3

This book has a fun premise. You’ve rented a time machine and then traveled into the distant past, but then it broke. You can’t repair the time machine, so you’re left to reinvent civilization from scratch. Where should you start? The book begins with five fundamental technologies:

- Spoken language

- Written language

- Non-sucky numbers

- The scientific method

- Calorie surplus

From there, the book progresses through all major technologies, from animal husbandry and agriculture to radio and computers. It’s an excellent bird’s eye view of the technological advancement of humanity, and all written at a level at which one could conceivably implement. After all, many of our advancements were just trying a bunch of things that didn’t work until we found something that did. This book is like a cheat sheet which would help you skip a lot of the trial and error.

The book also exposes just how much trial and error there has been. I was amazed at the number of technologies we had the building blocks for but that went undiscovered for millennia.

On top of all of that, it’s a fun, fast read. If you liked the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (and who didn’t?), you’ll love this.

The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads

by Tim Wu, finished January 8

Ever since I opened the magazine Adbusters 15 years ago, I’ve fostered a growing contempt for advertisements. And as advertisers and their clients find more and more ways to work their way into our lives, I’ve felt an increasing urgency to understand what they do and how they do it.

This book follows the course of advertising from posters in 19th century Paris to ads on Facebook. And while the medium has changed over and over, the purpose remains the same: to capture your attention and deliver it to the client.

Wu is not anti-advertising in the same way that Adbusters is. Still, he makes a few important observations that resonated with me. The first is that it was once considered unthinkable that one would be subjected to advertisements inside their own home, as private a space as any of us have. Now we don’t even think about it. Wu writes:

“Over the coming century, the most vital human resource in need of conservation and protection is likely to be our own consciousness and mental space.”

To that end, consider installing an ad blocker (like uBlock Origin) or finding other ways to remove ads from your life. Yes, our entire media landscape is held up by advertising, and that media landscape is a critical part of a functioning democracy, but what use is democracy if you (or at least your attention) has already been sold? Advertising is one business model – there are plenty of others.

★ When Breath Becomes Air

by Paul Kalanithi, finished January 14

This memoir chronicles the final years and days of Paul Kalanithi, a brain surgeon who was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2013 and died in 2015 at the age of 37.

Before his death, Kalanithi wrote the following about his book: “It’s just tragic enough and just imaginable enough. [The reader] can get into these shoes, walk a bit, and say, ‘So that’s what it looks like from here…sooner or later I’ll be back here in my own shoes.’”

That’s exactly what I took from the book, and it was depressing. Kalanithi’s final moments (as described by his widow in the book’s Afterward), in which he asks to lay next to his wife and eight-month-old daughter one last time, made me cry. It was the first time since Idara was born. We found ourselves all laying in a hospital bed together, too, though to mark the beginning of life, rather than its end.

Empire of Illusion: The End of Literacy and the Triumph of Spectacle

by Chris Hedges, finished January 17

This book presents the most damning evaluation of American culture and politics I’ve ever read, and it was written in the halcyon days of 2009. Imagine the same book written today. Anyway, the case he makes is a simple one:

“The worse reality becomes, the less a beleaguered population wants to hear about it, and the more it distracts itself with squalid pseudo-events of celebrity breakdowns, gossip, and trivia. These are the debauched revels of a dying civilization.”

Some of the “illusions” he presents include professional wrestling and daytime talk shows (the illusion of literacy), pornography (the illusion of love), elite higher education (the illusion of wisdom), and positive psychology (the illusion of happiness).

While reading this book I had to keep two facts balanced in my mind at the same time: that every civilization eventually meets its end, and that every time someone has predicted ours they’ve been wrong.

I don’t know if Hedges is right, but I do think that with each passing year we inch closer to the dystopia described in the film Idiocracy.

One thing that bothered me about the book was that Hedges spent 200 pages decrying the state of our country, the only solution he proposes, in the final two pages, is to remember the power of love. I don’t disagree that love is a transformative force, perhaps the transformative force. But how will love save a dying culture? I’m not saying it can’t, just that he ought to have explained how.

★ Blankets

by Craig Thompson, finished January 19

While on vacation with my good friend Mike, I told him that I’d never read a graphic novel. He pulled this one of the bookshelf of the house we were staying in and said, “Start with this one.” I’m glad I did. It’s not a novel, but a memoir of Craig Thompson’s youth, in which he struggled with love and religion.

The main marker on which I judge what I read (and write) is: Is this true? Not just true as in made up of facts (lower-case ‘t’ true), but true in terms of its fidelity to the human experience (upper-case ‘T’ true). Obviously this quality is dependent on the reader. So as a reader of this book, I found much that mirrored my own experience. And if you’ve never read a graphic novel, follow Mike’s advice. Start with this one.

Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades

by Steve Solomon, finished February 1

Every year that I’ve spent growing food I’ve read this book from cover to cover and back again. It’s my go-to reference, and I go to it over again throughout the season. If you’re growing vegetables in Western Oregon or Southwest Washington (i.e., west of the Cascades), I doubt you’ll find a better book.

The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics

by George Gheverghese Joseph, finished February 11

This book formed the lion’s share of an independent study I completed this winter on the history of mathematics. Several of my assignments for that course consisted of writing blog posts about the book, which you can find here.

The best books are those that forever change your perspective on a subject, and this book did exactly that. I knew there were mathematicians before the Greeks, but I was completely unaware of the contributions of the Indians and Chinese, and others, and how the math we practice today was so heavily influenced by these other cultures. And beyond demonstrating the depths achieved by other cultures and the connections to our own, Joseph shows that numeracy, like music and the spoken word, is culturally universal.

★ The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters

by Priya Parker, finished February 20 I’m not what Parker describes as a “gatherer.” I could probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve single-handedly organized a party or get-together. But after listening to an interview with Parker on J.K. Glei’s podcast, I wanted to be. Of course, we’re all gatherers at some point or another. We plan weddings, birthday parties, funerals, and so on, and this book advocates for doing it well.

Note that this is not hors d’oeuvre and flower arrangements. It’s about how to give meaning to your gathering. While I don’t have any big plans, I can think of lots of applications for the ideas in this book: birthday parties, anniversaries, and so on. Not to mention the fact that I’ll be teaching again soon. And what’s a class if not a gathering around a common purpose?

The Communist Manifesto

by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, finished March 11

I was waiting for another book to be ready at the library and found this one for free. I’d read it back in college but thought that it was worth another look since we have socialists running for president. Interesting how little capitalism and its critiques have changed in 170 years.

★ Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

by Cal Newport, finished March 13

I often feel like an outsider in the world of programming and computers because I’m convinced that a lot of digital technology is making the world (and us) worse, not better. But I still love programming, and computers, and many of the things that technology makes possible. The fact that this book is written by a professor of computer science gives makes it much more convincing.

The central theme of the book is that we ought to be extremely picky about the technology we let into our lives then we must optimize our use of it. This is a journey I’ve been on for years. In fact, many of the stories in the book about how people have gotten a grip on their technology use could’ve been lifted from my life. But like I said, it’s a journey. Reading books like this from time to time offer lots of important reminders.

Even though a lot of this book was old news to me, it still spurred a few changes. After finishing it I deleted my Facebook and Instagram accounts. I hadn’t been using them much for the past year or so anyway out of the strong conviction that they actually made me feel less connected and happy. Even so, after reading about how dramatic the difference is in the mental health of kids born before and after ubiquitous social media, I just didn’t want to be a part of it anymore.

Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results

by James Clear, finished April 8

This short book focuses on leveraging habits in the service of goals. The central tenet is that habits are broken into four parts: cue, craving, action, reward. If you want to maintain a habit, make the cues obvious, the cravings attractive, the actions easy, and the reward satisfying. To break a habit, make the cue invisible, the craving unattractive, the action difficult, and the reward unsatisfying.

A positive habit I’ve been maintaining recently is running in the morning two or three times a week. The cue is obvious because as soon as I wake up I see my running clothes set out and ready to be put on. The craving is attractive because I know that even though running sucks, I feel really good afterwards. The action is easy in the sense that I know that once I put on my running shorts, everything else is just going through the motions. And the reward – having gone for a run – is one of the best rewards there is.

A negative habit I’ve broken (for now) over the past year is dicking around on the internet. The cue was a moment’s boredom, which is hard to get rid of, and I honestly didn’t do much about the craving. The key was to make the action all but impossible: I deleted my Facebook and Instragram accounts and blocked all time-wasting websites (reddit, news, etc.) except for a few minutes in the evening. The block expires at 7:30 p.m. each night when Idara goes to bed, but most nights I don’t even remember to take advantage of it.

I created and broke the habits above before reading this book, but they map perfectly to what the author has to say. And anyway, it’s hard to imagine getting good at anything without breaking it down into habits and following through on them every day.

Rejection Proof: How I Beat Fear and Became Invincible

by Jia Jiang, finished April 18

The author, an aspiring entrepreneur, suffers from a crippling fear of rejection, so he decides to do something about it. He sets out on a quest to make dozens of ridiculous requests of strangers in hopes of getting used to rejection. He asks a man to photograph him playing soccer in the man’s backyard. He asks strangers for money. He asks to make the safety announcement on an airplane. And on and on.

It is, admittedly, a little dumb. But it also spoke to me. Like Jiang, I think that a fear of rejection plays a large role in my life, and so this book has me thinking about ways to overcome it.

When Strangers Meet: How People You Don’t Know Can Transform You

by Kio Stark, finished April 20

This short book is a kind of celebration of talking to people you don’t know. I’m often buoyed by interacting with strangers, and I thought this book did a nice job of capturing why. I only wish it were longer.

★ Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City

by Matthew Desmond, finished April 27

Simply the best portrait of American poverty I’ve ever read. Heartbreaking, inspiring, and a testament to the power of ethnography. Of all the books I’ve read so far this year, I expect that this one will stick with me the longest.

This Is Marketing: This is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn To See

by Seth Godin, finished May 3

I can’t stand advertising, but somehow I’m drawn to books about marketing. Probably because at its heart it’s really about clear and effective communication. Anyway, I liked this book.

The main takeaway, for me, is this: rather than trying to be all things to all people, just try to be really perfect for the people you serve. Whether they’re your students, your customers, or your readers. Which I guess means that I need to focus on you, dear reader.

TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking

by Chris Anderson, finished May 11

When I participated in a group interview at Lewis & Clark’s Graduate School of Education and Counseling, I found that I wasn’t as strong a public speaker as I’d like to be. So I started attending a Toastmaster’s meeting downtown. My school schedule dictates that I probably won’t be able to keep it up all year, but it’s been an incredible experience thus far.

This book, which I picked up for the same reasons, was good. Apparently there aren’t a ton of great public speaking books out there, but this one was good. I’d read it again.

The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure

by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff, finished May 23

This book attempts to make the case that something is rotten in American colleges – not student debt, or mass shootings - but that today’s college students refuse to engage with ideas they disagree with. They create safe spaces, the authors argue, and demand trigger warnings.

While I don’t doubt that these practices exist, it seems like the authors are creating a (best-selling) mountain out of a molehill. If there’s data to back up the idea that safe spaces are the problem the authors make them out to be, they didn’t share it. And as for their supposed refusal to engage with ideas they disagree with, college students aren’t so different than the rest of us. See Fox News, MSNBC, and basically the rest of the well-sorted American media landscape.

While I believe in the freedom of speech, I’m skeptical of the pro-speech argument that the only thing preventing us from solving the world’s problems is sitting down with our enemies and talking things out. As I once read on Twitter: “Slavery was abolished by those great debaters Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman.” In other words, a reasoned debate didn’t settle slavery in the United States – it took a civil war.

The authors, to their credit, do make a good case for the importance of the open exchange of ideas, and it was these parts (along with an endorsement of free-range parenting and Stoicism) that made me glad I read the book.

Do You Talk Funny?: Seven Comedy Habits to Become a Better (and Funnier) Public Speaker

by David Nihill, finished May 25

More about public speaking than about comedy, but just as well, since that’s why I decided to read it in the first place. Main takeaway is this: practice, practice, practice. He quotes Steve Martin: “Persistence is a great substitute for talent.”

Not sure if it’s true or not, but the author, a standup comedian himself, says that it takes about 22 hours for a professional comic to prepare one minute of material.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

by Yuval Noah Harari, finished June 7

This was a fascinating (and depressing) book. The author takes the perspective that the Agricultural Revolution was a mistake (because it isolated us from nature), and similarly with the Industrial Revolution (because it isolated us from each other). I don’t necessarily disagree, depending on what metric one uses to judge, but seeing it framed so succinctly was depressing.

Another thing that was depressing about this book was the way that it frames the meat and dairy industry as perhaps the greatest injustice ever perpetrated by mankind. I’ve grown increasingly uncomfortable eating meat and cheese since Idara was born (which maybe someday I’ll explain in another blog post), and so these parts got me thinking again.

The Mueller Report: Executive Summary

by Robert Mueller, finished June 8

At 26 pages, this isn’t exactly a book, but I wanted a record of having read it, and so I’m including it here. First of all, if you haven’t read it, you should (here’s the text itself - you can also find Kindle and ePub versions by clicking here).

The report focuses on two potential crimes related to President Trump: coordination between the Trump campaign and Russia with regards to election interference, and obstruction of justice.

On the first topic, Mueller and his team determined that while Trump benefitted from the interference, and that there were numerous contacts between his campaign and Russians connected to the illegal operations, their contact didn’t rise to the level of being prosecutable.

Mueller is somewhat more vague on the second topic. After making clear that Justice Department rules bar the special counsel from charging a sitting president, the report goes on to state:

“…if we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the President clearly did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state. Based on the facts and the applicable legal standards, we are unable to reach that judgment.”

Seems about as damning a determination as they could’ve made.

On a somewhat related note, I think it’s funny that I spent hours and hours and hours following this story from its origin back in 2016 to the present. And yet I could’ve saved all that time (and hand-wringing!) by just reading this. You live and you learn.

The Art of Community: Seven Principles for Belonging

by Charles Vogl, finished July 3

I picked up this book in hopes of better understanding the time I spent in Doha, in which I felt part of a close and vibrant community. Looking forward, I’d hoped that the book might help me cultivate a strong community in the classes of which I’m a teacher. A takeaway:

“Because members share values, the community helps answer three important questions for members in some way: Who am I? How should I act? What do I believe?”

Birth Partner: A Complete Guide to Childbirth for Dads, Doulas, and Other Labor Companions

by Penny Simkin, finished August 12

Idara’s birth took us by surprise and so I never had time to read a book like this. When Rachael was laboring I just did the best I could and followed the direction of the nurses, who were great. I wanted to to be more prepared this time around, so I checked this book out from the library. It covers everything that can happen during the birthing process, and so is helpful as a survey of the range of possibilities. It also focuses on rhythm, ritual, and relaxation as the keys to laboring productively. I photocopied about a dozen pages and will keep them with me as a reference.

Sweet Dreams, Story Catcher

by Brian Doyle, finished August 14

On my first as an intern at Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Think Out Loud, I watched Bryan Doyle read “Leap,” a short piece about people jumping from the twin towers as they burned. It’s mesmerized me ever since, and have made a tradition of listening to it on September 11th.

Before he died in 2017, Doyle wrote for the University of Portland. This book is a collection of those essays, spanning topics as wide as Catholicism, fatherhood, alcoholism, the natural world, and on and on. I put a little sticky note on each essay that spoke to me, and by the time I’d finished I found that I’d marked nearly every page. If there was ever a writer whose voice I wanted to capture, Brian Doyle’s is it.

Turtles, Termites, and Traffic Jams: Explorations in Massively Parallel Microworlds

by Mitchel Resnick, finished August 26

I read this on an off-hand recommendation from one of my teaching mentors. It was written by Mitchel Resnick, one of the creators of the programming language Scratch. This book is centered on StarLogo, another language he created in the mid-90’s to model cellular automata. It brings together a few ideas into a short yet thought-provoking book: modeling the physical world with computers, learning through programming, and the trend (in the mid-90’s at least) toward decentralization. Here’s my favorite line from the book:

“Too often, schools give special status to particular ways of thinking about mathematical and scientific ideas. By privileging certain types of thinking, they exclude certain types of thinkers.”

I found the book inspiring enough that it forced me to break out my Arduino and soldering iron and build an LED representation of the cellular automata classic, Conway’s Game of Life.

Nix the Tricks: A Guide to Avoiding Shortcuts That Cut Out Math Concept Development

by Tina Cardone, finished September 12

Much of the math I learned growing up was focused on picking up tricks rather than on understanding the underlying concepts. A good of example of a “trick” is many people (including myself) go about dividing two fractions, say ½ ÷ ⅔. The trick, as I learned it, is to multiply the first number by the reciprocal of the second number, resulting in ¾. The reason this works is because we’re basically finding a common denominator with a multiplication operation in the numerator.

That’s just one example. This book is filled with tons of “tricks,” the concepts which they’re based on, and how to teach the concepts in stead of the tricks.

Markings

by Dag Hammarskjöld, finished September 18

This was not my favorite book of the year, but there was still value in reading it. For one, it provided an opportunity to learn about the life of Dag Hammarskjöld, Swedish diplomat and second secretary-general of the United Nations. The book isn’t much of a book at all, really, more a collection of thoughts on death, overcoming hardship, vanity, and other topics.

A favorite line: “Do not look back. And do not dream about the future, either. It will neither give you back the past, nor satisfy your other daydreams. Your duty, your reward – your destiny – are here and now.”

Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World – and Why Things Are Better Than You Think

by Hans Rosling, Anna Rosling Rönnlund, and Ola Rosling, finished September 21

The crux of this book is that despite what we see on the news, the world is actually steadily improving. That is not to say that things are good, just that they’re getting better. I was skeptical of the premise and almost gave up after the first few pages. I’m glad I stuck with it.

The most memorable part of the book is the process of categorization of the world into four levels, rather than the usual binaries of developed/developing or first/third. Each level has its markers. For example, on level one people get around on their feet. At level two they might have a bicycle or pack animal. At level three people will have access to small motorized transport, like a motorcycle or a moped. At level four, people drive cars. Or for dental hygiene: Level one means using a stick or rag to brush teeth. Level two means that you have a toothbrush but you share it with other people in your family. Level three means you get your own toothbrush, and at level four it’s electric.

“Without world peace, you can forget about all other global progress.”

The overarching theme of the book is that people are, in general, moving up these levels rather than down. I won’t attempt to make the case here, but I will say that if you’re curious, read the book. It’s worthwhile.

On climate change, the authors write: “In these circumstances, it is a testament to the blame instinct how easily we in the West seem to shift responsibility away from ourselves and onto others. We say that “they” cannot live like us. The right thing to say is, “We cannot live like us.”

★ The Unsettlers: In Search of the Good Life in Today’s America

by Mark Sundeen, finished October 9, 2019

When I was in college I read The Unsettling of America, written by Wendell Berry (who was recently profiled by Vox), which argued for a renewed focus on rural and agrarian life as the solution to America’s problems. This book, published forty years later in 2017, profiles three couples who are trying to put Berry’s ideas into practice. One couple lives in rural Missouri, another in Detroit, and the third outside of Missoula, Montana.

I’ve long romanticized moving “back to the land,” but I’m now old enough to know that I’m not enough of a zealot to make it work. I think I’d be happy with a garden and a goat or two. With that in mind, I loved this book for its realistic assessment of the triumphs and struggles faced by these people. And the writing was top notch, too. A bit like The Unwinding, by George Packer, which remains one of the best non-fiction books I’ve ever read.

Dive Into Inquiry: Amplify Learning and Empower Student Voice

by Trevor McKenzie, finished November 27

I picked up this book to learn more about inquiry-based teaching and I only wish it were longer and more comprehensive. One of the interesting practices that the author proposes is including students in designing the course at the beginning of the term. Of course there are certain things that must be covered, about which the author writes:

“All courses include a particular amount of ‘must-know’ material determined by our respective governing bodies of education. My job during the course co-design is to ensure this must-know material is included in our plan.”

He also stresses a scaffolded process of integrating inquiry-based learning:

- Structured Inquiry: Students follow the lead of the teacher as the entire class engages in one inquiry together.

- Controlled Inquiry: Teacher chooses topics and identifies the resources students will use to answer questions.

- Guided Inquiry: Teacher chooses topics and questions while students design product or solution.

- Free Inquiry: Students choose topics without reference to any prescribed outcome.

One example he sites of free inquiry was a student who wanted to build a project out of rebuilding an old amphibious vehicle called a Bazoo. Another student made a project out of becoming trained as an EMT. These students then presented their work to the rest of the students when they were finished. It’s hard to imagine designing a lesson for these students which would’ve been more interesting than that.

★ Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace

by Brian Doyle, finished November 28

I just can’t get enough of short stories by Brian Doyle. I doubt they would’ve resonated before becoming a father, but they certainly resonate now.

The World Without Us

by Alan Weisman, finished December 5

One of the most interesting books I read this year. The premise is that humans have just disappeared from the earth (via the rapture, or alien abduction, or a fast and fatal flu). What happens to our homes? Our cities? Our nuclear power plants? Our plastics and cement and bronze and wood? Rather than just say “first x, then y, then z,” he dredges up examples of times when these things have come to pass in miniature: the Chernobyl meltdown, for example, or Varosha, a city in Cyprus that was completely abandoned during the country’s civil war in the mid-70’s. Here’s one of my favorite lines, about the fall of the Mayan Empire:

“Nobility is expensive, nonproductive, and parasitic, siphoning away too much of society’s energy to satisfy its frivolous cravings.”

The Tao Te Ching

by Lao-tzu, translated by Stephen Mitchell, finished December 23

Written in the 6th century BCE (we think) by the Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu (we think), this book is comprised of 81 short, untitled chapters, each with a few statements about the nature of the Tao, which Merriam-Webster defines as “the unconditional and unknowable source and guiding principle of all reality” and Wikipedia calls the “way.”

To give you a sense, here’s one of my favorites:

Men are born soft and supple;

dead, they are stiff and hard.

Plants are born tender and pliant;

dead, they are brittle and dry.Thus whoever is stiff and inflexible

is a disciple of death.

Whoever is soft and yielding

is a disciple of life.The hard and stiff will be broken.

The soft and supple will prevail.

Keep Going

by Austin Kleon, finished December 26

This book is filled with encouragement and ideas for creative types – artists, writers, etc. It’s similar to Kleon’s other two books Steal Like an Artist, and Show Your Work. It was a quick read (a couple hours at most) but I love his perspective on the creative process. In a sentence:

“I don’t want to know how a thirty-year-old became rich and famous; I want to hear how an eighty-year-old spent her life in obscurity, kept making art, and lived a happy life.”

The Life You Can Save

by Peter Singer, finished December 30

Earlier this year I became familiar with the effective altruism movement via the Vox podcast Future Perfect. The central idea of effective altruism is doing the most good with the time and money you have. This book, written by the same man who kicked off the modern animal welfare movement in the 1970’s with his book Animal Liberation, is a bit more narrowly focused on ending extreme poverty via financial contributions. In it, he makes the case that we in rich countries should be donating a percentage of our income every year to solve this problem. I have a lot of thoughts about this and hope to share them in a future post.

If you’re interested in the book you can download it for free (either as ebook or audiobook) from The Life You Can Save.

Fiction

Americanah

by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, finished February 5

Last year I decided that I’d like to read more fiction, and this is where I started. The novel follows the lives of Ifemelu and Obinze, two Nigerians who eventually leave their country in search of something better.

I have more to say about this book than time to write it down, but the main takeaway for me was that you learn more about yourself (or your country) from outsiders than you can from yourself, and you learn more about yourself as an outsider than when you’re among your own people. With that in mind, Adichie’s novel is an excellent education.

Fahrenheit 451

by Ray Bradbury, finished February 12

I never read Fahrenheit 451 in high school and so all I knew was that it was about a world in which books are burned. But it’s not so much a defense of books as it is a defense of books as a medium for connecting us to one another. Bradbury writes:

Books were only one type of receptacle where we stored a lot of things we were afraid we might forget. There is nothing magical in them, at all. The magic is only in what books say, how they stitched the patches of the universe together into one garment for us.

So books connect us to one another and serve as an antidote to alienation. But other things can, too. Indeed, one of the most affecting parts of the book is in the early pages where Montag, the protagonist, meets a neighbor who spends long hours simply lost in thought, rather than watching soap operas. It’s this meeting that allows Montag to realize the problems of the world around him, and it has nothing to do with books.

All the Birds in the Sky

by Charlie Jane Anders, finished March 3

I’m always a little hesitant to read random books I don’t know anything about, but since this book was a gift from someone who knows me well, I decided to give it a shot. Although I found the finish less than satisfying, I did like how the author slipped in subtle science-fiction.

Early on, one of the characters finds that she can converse with birds, but only every once in a while and never when she wants to. Another character builds a watch that allows him to travel forward in time, but only by two seconds. Good examples of how a story doesn’t have to be over the top to be engaging.

★ Never Let Me Go

by Kazuo Ishiguro, finished March 20

This is my favorite novel so far this year. I read it not knowing anything about the plot, and I think you should too, so I won’t talk about it here.

After finishing it I read a bit about what the lives of the protagonists are meant to represent. Two suggestions I found interesting: that their lives are an allegory on aging, or that they’re an allegory on the meat and dairy industries. Neither of these topics are mentioned in the book, but thinking through the implications was one of my favorite parts about having read the book.

Cloud Atlas

David Mitchell, finished April 3

This was a long one. There were parts that I really enjoyed, but as many parts (or more) that were dead weight. I’m glad I read it, if only for the good parts and not for the story as a whole.

Station Eleven

Emily St. John Mandel, finished April 17

I bought this book for the premise. A mysterious illness has wiped out all but a tiny fraction of Earth’s population, and a girl makes her way in the aftermath. Unfortunately, the premise was just about the only thing I liked about the book.

The author did a wonderful job imagining a realistic post-apocalyptic future (though I would’ve expected more English Ivy). But the story itself was lackluster. I just never really cared about any of the characters or what they got up to.

★ The Road

by Cormac McCarthy, finished May 23

I picked this book up about ten years ago but was so turned off by McCarthy’s writing style that I couldn’t get past the first few pages. There’s hardly anything in the book at all – just a steady stream of occurrences with a few dreams and flashbacks mixed in. Plus there are no quotation marks, so the dialog is difficult to follow.

Then I saw the movie and loved it. It’s impossible to imagine any writer or director ever painting a darker scene. So I decided to try it again, and this time I loved the book, too. One of my favorite lines:

“All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain. Their birth in grief and ashes. So, he whispered to the sleeping boy. I have you.”

I used to think that the book was about the apocalypse, but it’s really about being a father. Maybe the subjects aren’t so different.

The Remains of the Day

by Kazuo Ishiguro, finished June 16

I had high expectations for this book. For one, it won the Booker Prize, and two, it’s by the same author as Never Let Me Go, which I read earlier in the year and has proven to be one of the best novels I’ve ever read. The Remains of the Day is similarly spare, in the sense that one can read into a variety of different themes and messages, some of which are contradictory. The central question, for me at least, is the one it raises about the duty one should feel to their employer. As an answer to this question, I think it’s a good book, though not great.

Lincoln in the Bardo

by George Saunders, finished July 18

This book won the Man Booker Prize when it came out in 2017. It was weird. Told from the perspective of over one hundred different characters, the book tells the story of Willie Lincoln immediately after his death. More about the book here.

I was initially attracted by the strangeness of the title, and then found that I liked the first few pages. There were parts where the story was hard to follow because of the way it was conveyed, but it was strange and entertaining and I’m glad I read it.

The Pearl

by John Steinbeck, finished July 31

I was discouraged by the fact that I’d completely stopped reading for myself once I started classes at Lewis & Clark, so I picked up this novella about a pearl diver who finds a very valuable pearl. Eventually I’d like to read everything written by Steinbeck. In addition to The Pearl I’ve read The Grapes of Wrath, East of Eden, and Travels with Charley.

As I Lay Dying

by William Faulkner, finished October 13

My second Southern Gothic of the year, after Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Like that book, the descriptive language is what stood out to me about this book.

“Jewel and Vernon are in the river again. From here they do not appear to violate the surface at all; it is as though it had severed them both at a single blow, the two torsos moving with infinitesimal and ludicrous care upon the surface. It looks peaceful, like machinery does after you have watched it and listened to it for a long time. As though the clotting which is you had dissolved into the myriad original motion, and seeing and hearing in themselves blind and deaf; fury in itself quiet with stagnation.”

The Dog Stars

by Peter Heller, finished December 23

Several of the novels I’ve read this year have been set in a post-apocalyptic world: The Road, Station Eleven, and now this one from Peter Heller. Told from the perspective of a Cessna pilot who befriends a gun nut, it’s part drama, part comedy, part romance. All in all I enjoyed reading it, though it pales in comparison to The Road, which might be my favorite from this year.

Poetry

Wild Honey, Tough Salt

by Kim Stafford, finished August 28

When Rachael and I were living in an old house on Hancock Street, I used to keep Leaves of Grass on the breakfast table and read a poem while I ate toast. That’s the last time I remember reading much poetry, and so this book, gifted by Rachael’s aunt, was a reintroduction. One of my favorite lines, from “A List of Wonders from the Times of Small”:

“A door opens, closes. A book opens, closes. Morning makes light, and evening takes light away.”

There were quite a few that I liked. Among them:

- “Milk”

- “August, 1997”

- “Ten Years After the Last Words”

- “Love Money”

- “Home Alchemy”

One part that still has me thinking is the collection of poems about war. They’re written with a perspective and detail that had me wondering if Stafford had served in the military. I’m almost certain he didn’t, but it still gave me pause.

Children’s Books

Here are a few of Idara’s and my favorite children books that we read this year.

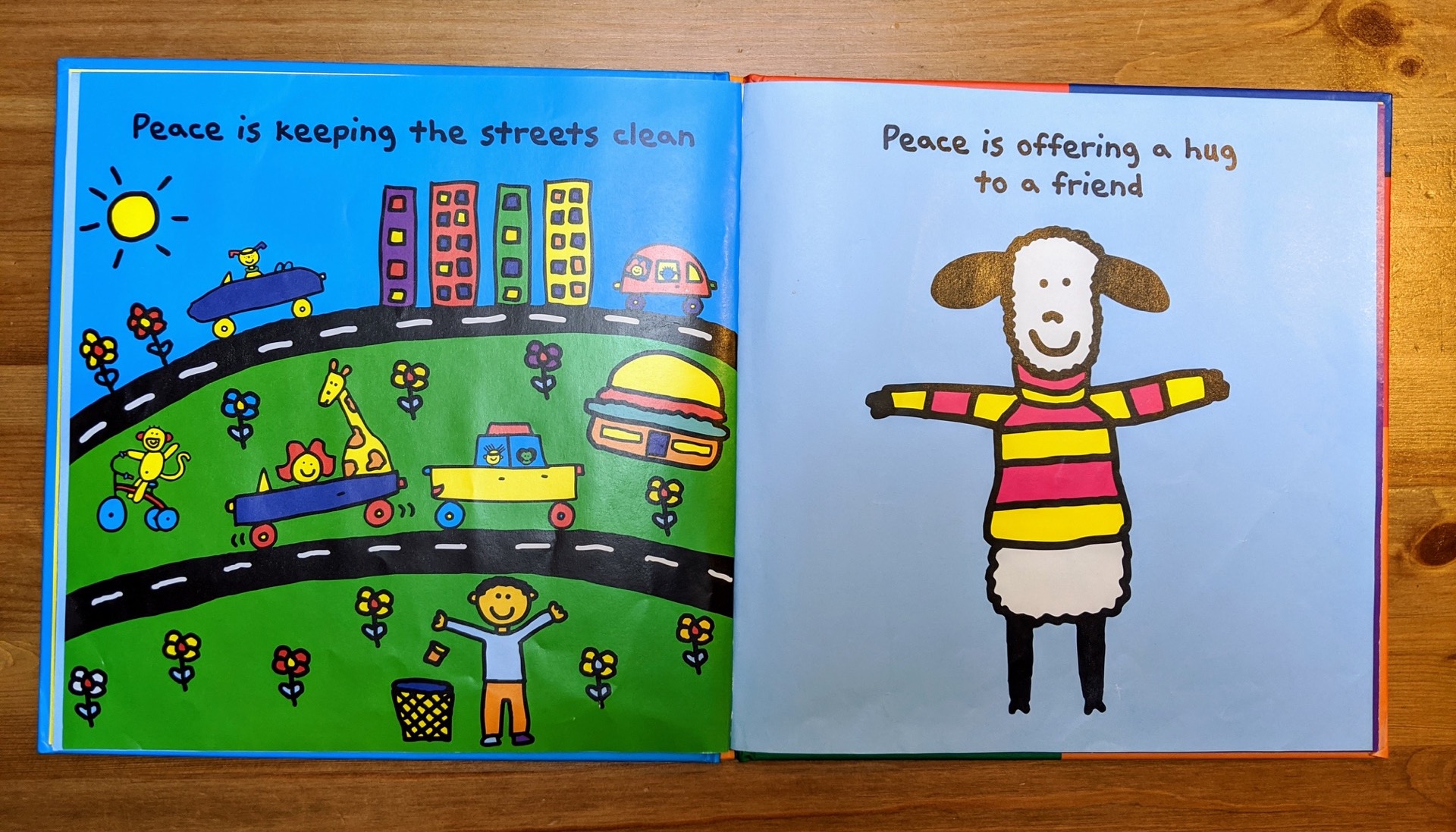

★ The Peace Book

by Todd Parr

I’m not sure what I like more about this book: the positive messaging or the drawings that appear to have been completed with MS Paint. Anyway, it’s hard not to like a book that finishes with language as simple and direct as this:

“Peace is being different, feeling good about yourself, and helping others. The world is a better place because of you.”

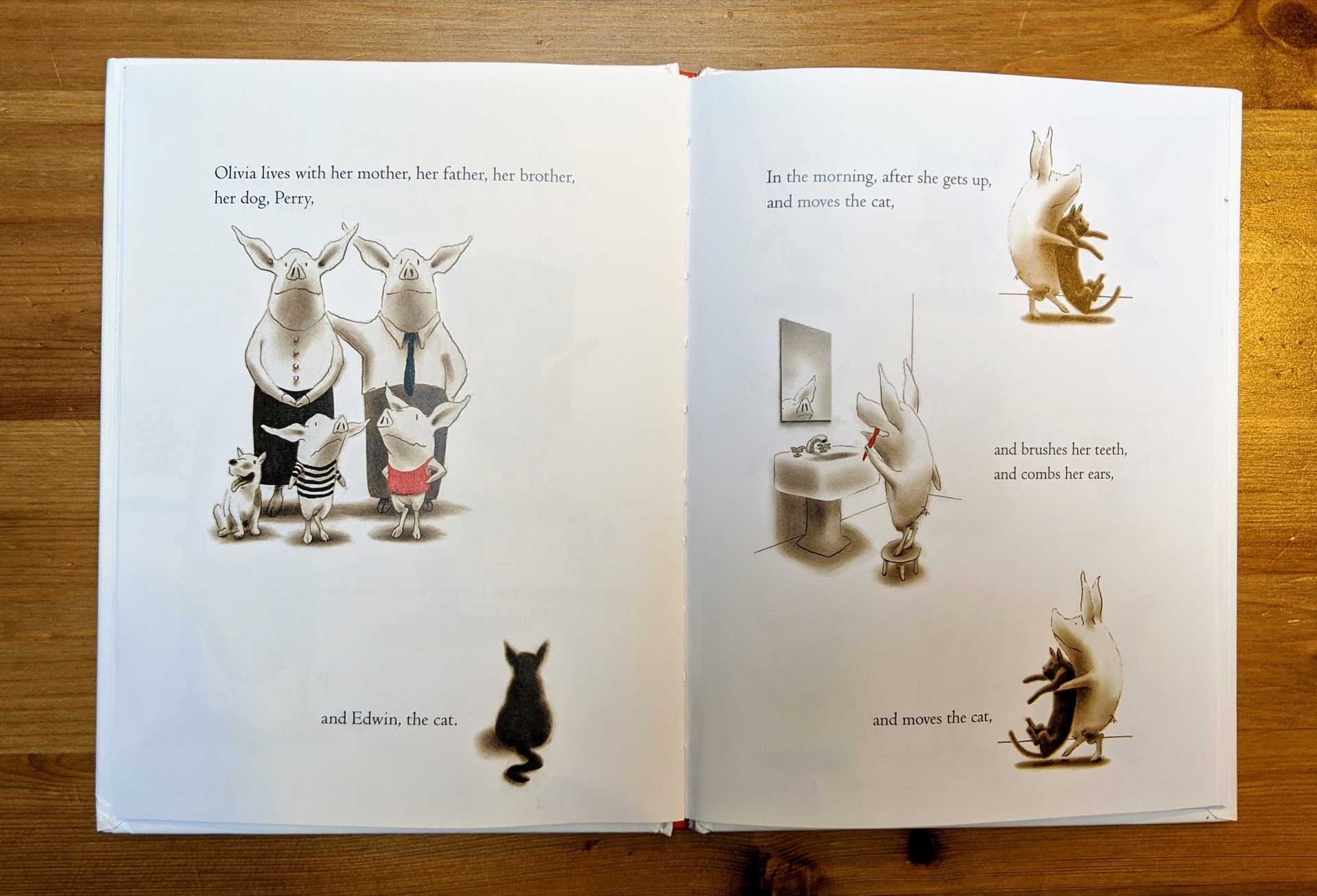

★ Olivia

by Ian Falconer

I know this book has been around for a long time, but it’s still great. I particularly like the drawings and how Falconer communicates a lot of ideas and emotion with very few words.

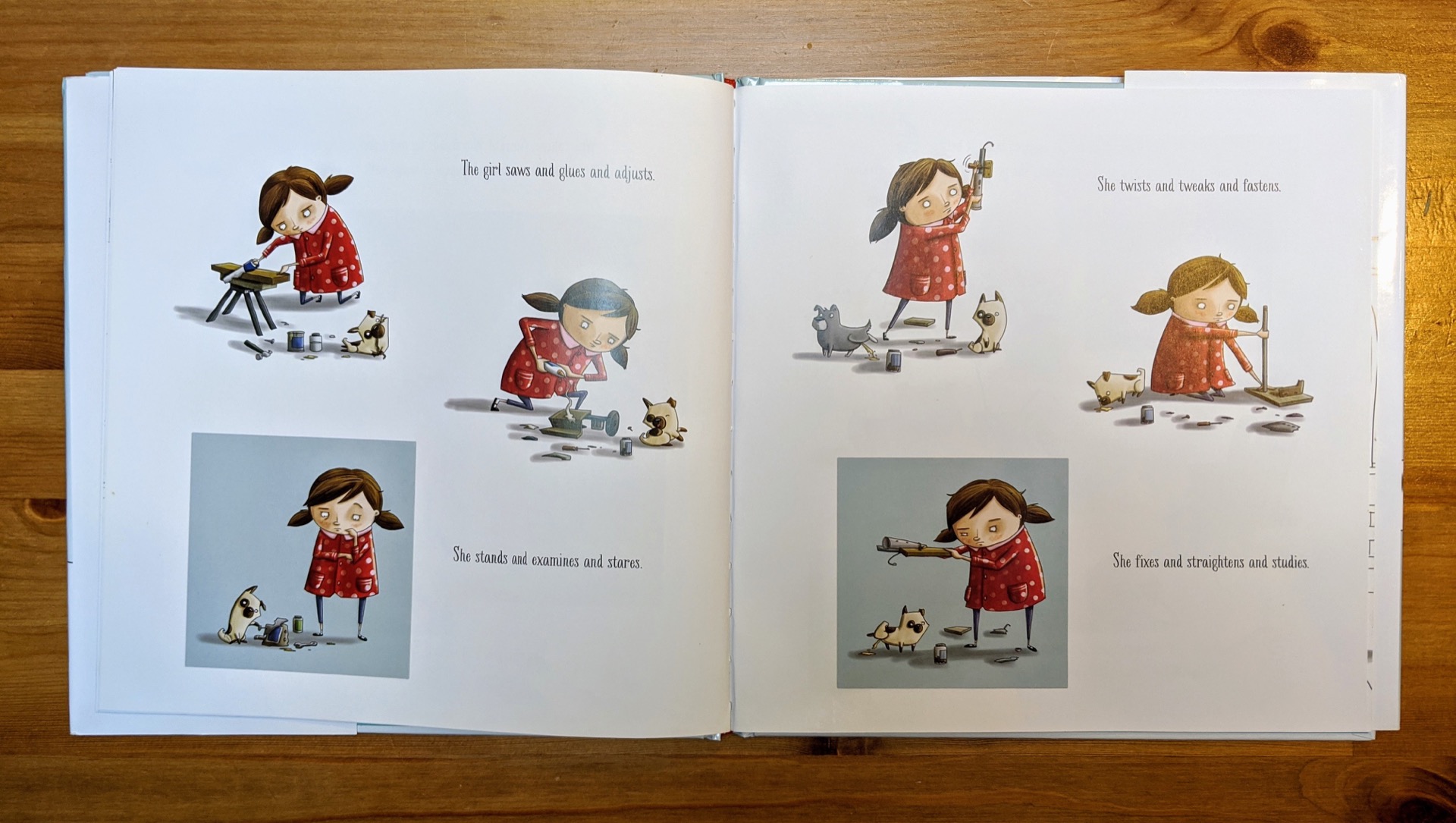

★ The Most Magnificent Thing

by Ashley Spires

This is obviously a book for kids, but it’s also one of the best representations of the design cycle (brainstorm → design → build → test) that I’ve come across. In particular, this book paints a very accurate picture of thrashing, which is unproductive or ineffective work. Best of all, this book is just an adorable little story about a girl overcoming the challenges that come with designing and building. Good illustrations, too.

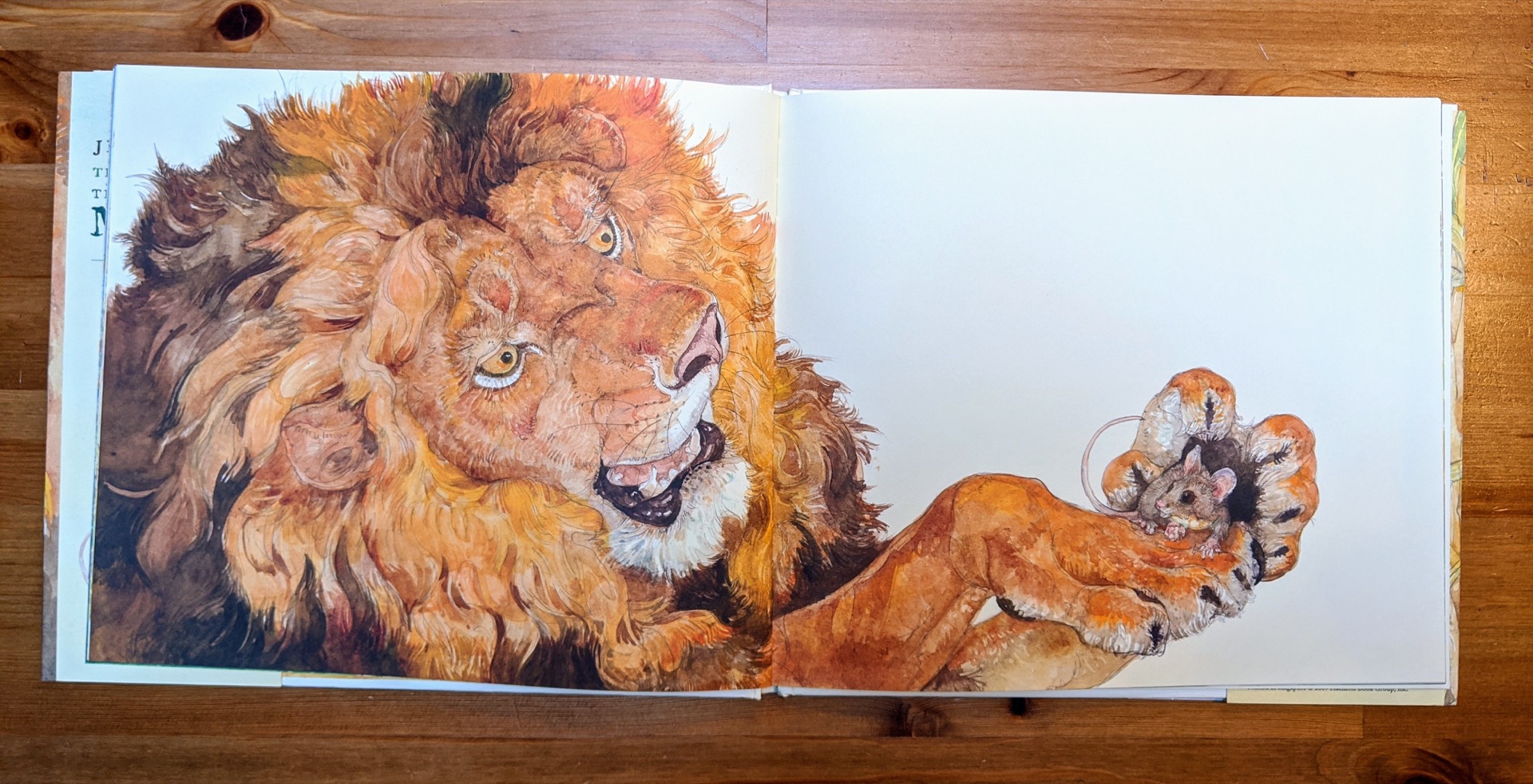

★ The Lion & the Mouse

by Jerry Pinkney

There are only a handful of words in this book, and no sentences, so when Idara wants to read this book out loud it’s up to me to describe what’s going on. Coming up with the words to a story can be pretty tiring at the end of a long day, but we’ve read this one enough times that it’s not too much trouble. And I also like that I can make the story a little different every time we read it. The real draw here, though, are the beautiful illustrations.

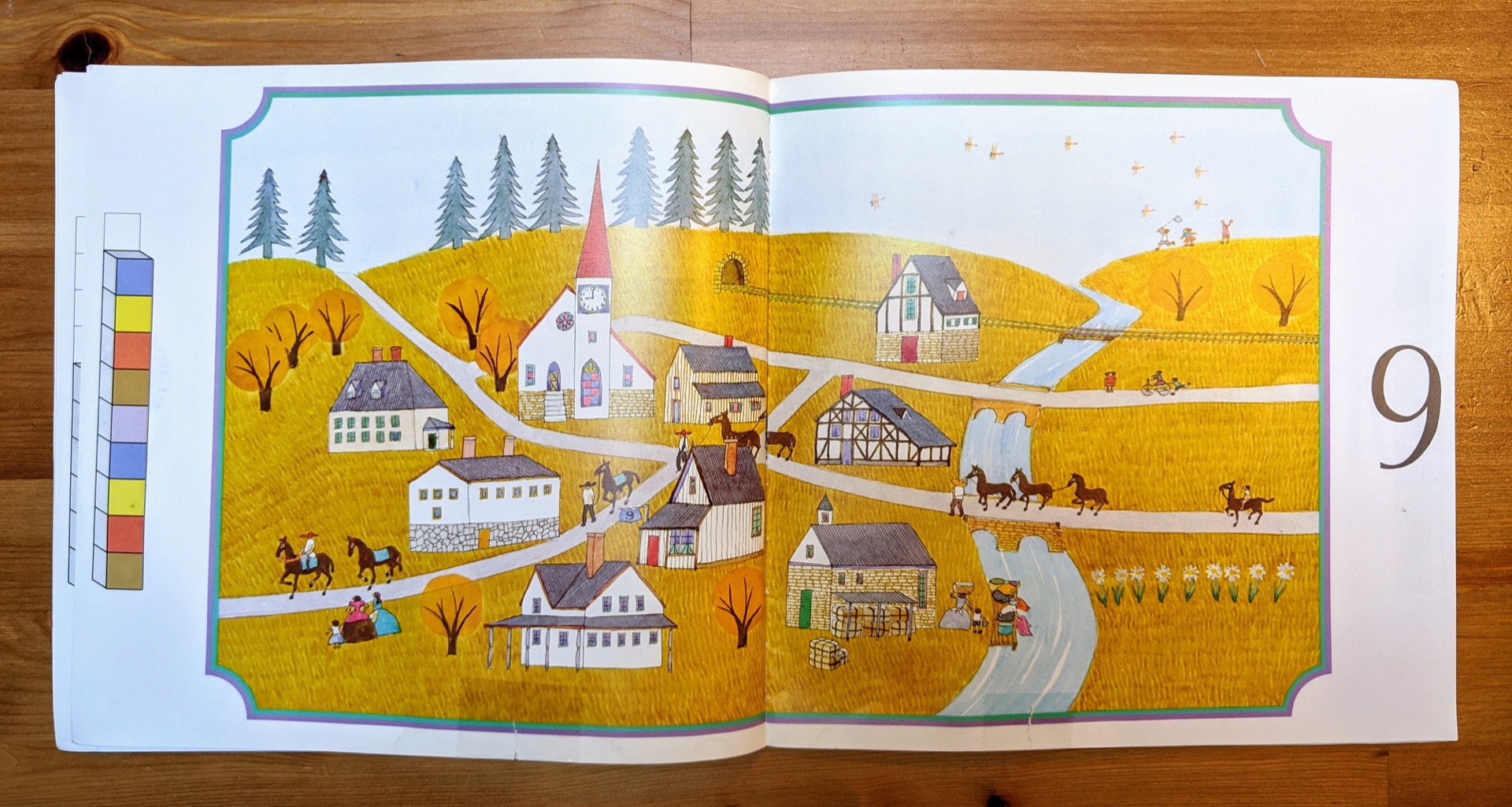

★ Anno’s Counting Book

by Mitsumasa Anno

Counting books are a dime a dozen, but this one is special. Instead of just presenting one thing on each page to count, this book is filled with them. It starts with an empty hillside to signify the number zero. The next spread pictures the same hillside but now with one of a variety of objects: one tree, one child, one bird, one cloud, and so on. It goes on like this until the twelfth spread (duodecimal!). What’s more, the book also tracks the months and seasons of the year. It’s great, and makes for a nice, calm book to finish with right before Idara goes to bed.