Instructor

Stephen Redfield

Topics

Each week of the course focused on a particular topic. Here they are, in order:

- Networking basics

- The Application Layer

- Socket programming and the Transport Layer

- The Network Layer

- The Data Link Layer

- Wireless and Mobility

- Network Security

Preparation

I didn’t prepare in advance for this course, but there is one topic which I wished I knew more about: sockets. More specifically, how to program sockets. Both projects in the class involved creating and connecting sockets, but the course doesn’t really teach this topic specifically. Instead, students are referred to Beej’s Guide, which I didn’t find very helpful. Thankfully, a friend referred me to Brewster’s excellent networks and sockets lectures from Operating Systems (344), which were incredibly helpful for both projects. To do it again, I would have worked through those lectures in advance in hopes that it would’ve made the projects themselves less stressful when it came time to complete them. And in case you’d prefer the PDFs, here they are.

Programming Environment

I wrote two programs for the course: a chat server in Python (host) and C (client), and an FTP-style file transfer server in C (host) and Python (client). I used CLion for the C code and PyCharm for the Python code.

There were several labs which didn’t involve programming, but did require the use of a packet sniffing application called WireShark.

Assignments

Having never programmed sockets before, I found the two projects quite difficult. However, there were three things that made the assignments less onerous than they would’ve been otherwise: starting early, taking breaks, and drawing pictures.

While completing the first assignment I found myself incapable of performing a particular manipulation on a C-string. Regardless of how hard I tried or how much I researched I simply could not figure it out. Fortunately, I had to step away from the computer in the middle of the day to go volunteer at a nearby high school. When I came back a few hours later, I solved the problem in a few minutes. So, start early so you have time to step away from the computer, and then actually step away from the computer. It’ll help.

This brings me to one of my chief criticisms of the class: that the assignments require writing sockets in C. Before you say, “You just want everything handed to you on a silver platter,” hear me out. Writing a socket in C isn’t fundamentally different or more difficult than writing a socket in Python. In fact, compare these two blocks of code:

C

int listenPort = atoi(argv[1]);

int listenSocket = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0);

struct sockaddr_in address;

address.sin_family = AF_INET;

address.sin_port = htons(listenPort);

address.sin_addr.s_addr = INADDR_ANY;

bind(listenSocket, (struct sockaddr *) address, sizeof((*address)));

listen(listenSocket, 5);

Python

LISTENHOST = ''

LISTENPORT = int(sys.argv[1])

LISTENSOCKET = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM)

SERVERSOCKET.bind((LISTENHOST, LISTENPORT))

SERVERSOCKET.listen(1)

Not so different, right? The only significant difference is that in C the address is a struct which must be constructed manually. So why, in the case of my FTP-style program, is the C code three times longer than the Python? The answer: C-strings. Well, C-strings and a bunch of other stuff. Surely if I were a better C programmer I could’ve written the program more tersely, but that’s beside the point, which is this: writing sockets in C brings in a bunch of overhead that isn’t related to sockets and didn’t allow me to understand sockets in any greater detail. It just renewed my hatred for C-strings.

If I were designing this course, I’d drop the C requirement and allow students to write their sockets in a higher level language, as long as that language was making the same calls to the sockets API. That way the assignment would actually focus on sockets, and not on the idiosyncrasies of manipulating strings in C.

Low-level badasses will probably disagree with my opinion that Python is a better language for learning sockets, and that’s fine. But let me try one more defense: Does opening a web browser teach you anything about sockets? Of course not, because it’s completely abstracted away. What about using an FTP program? No, although it reveals a little bit more about what’s going on behind the scenes. Will programming a socket in Python teach you anything about sockets? Definitely. What about programming a socket in C? Yep, although at this point you’re probably learning more about C than you are about sockets. Finally, what about programming a socket in Assembly? Now you’re definitely learning more about the language than sockets. Hopefully this illustrates my point. Python is a nice happy-medium level of abstraction between just opening up a browser and writing Assembly.

Finally, a note on drawing pictures. When I started programming Project 2 (the FTP program) I told myself that I would not let myself thrash. I’d make a plan, think clearly, take breaks, etc. So when I found myself thrashing on a Friday, which also happened to be my wife’s birthday, and the day that we were supposed to leave for a camping trip, I was even more frustrated than I would’ve been if it were just a garden-variety thrashing session. But like I said, we were leaving for a camping trip, so I had no choice but to put the computer away and give my subconscious a few days to sort it out. Thankfully I’d started early, so I didn’t have a deadline breathing down my neck.

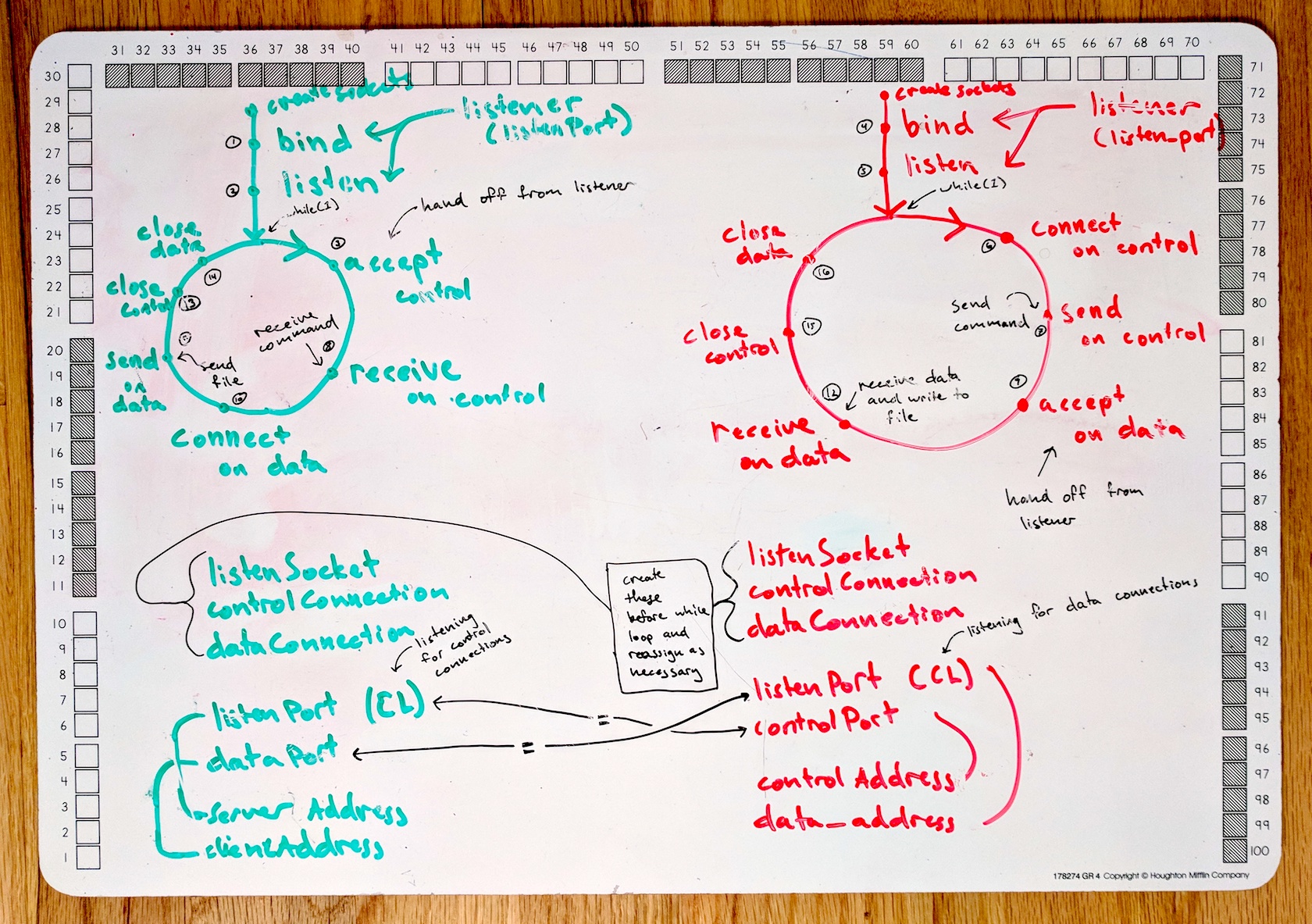

When I returned from the camping trip, the first thing I did was sit down on the couch and draw out a diagram on a whiteboard. It shows the socket setup and basic loops that the server and client traverse to accept connections and process requests.

This diagram models a server (in green) and a client (in red). The circled numbers (in black) represent the steps that the two programs follow to connect and transfer a file.

This diagram models a server (in green) and a client (in red). The circled numbers (in black) represent the steps that the two programs follow to connect and transfer a file.

This process of diagraming the pieces and how (and in what order) they fit together did wonders for my understanding of the program.

In summary: start early, take breaks, and draw pictures!

Quizzes

The weekly quizzes, called summary exercises, were a pain. But once I figured out a strategy for completing them, they became a great tool for understanding the material. Before I get to my strategy, two important points: first, each summary exercise was only worth one percent of the final grade, and second, I was allowed two attempts for each summary exercise. OK, here’s the strategy:

- Submit the first attempt without answering any questions. You’ll fail it, obviously, but you’ll gain valuable information in the process.

- Use your first failed summary exercise as a guide to what to focus on in the reading and lectures. Pay special attention to the explanations of the different calculations, which are easy to gloss over.

- Take the summary exercise a second time, hopefully improving upon the 0 percent you earned the first time around.

- Finally, save the questions and answers from both summary exercises in a flashcard program like Anki.

Exams

That last point above, about using a flashcard program, was basically my entire test strategy. Some classes lend themselves to the rote memorization that flashcards are designed for, and this is definitely one of them.

By the time the midterm came around I’d already amassed a few hundred flashcards, and studying was as simple as reviewing a few dozen of them each day. I never had to cram for the midterm nor the final, and I still did well on both of them.

In addition to the flashcards, I prepared a simple cheatsheet with formulas and made sure I was comfortable using my TI-89’s built in decimal to binary to hexadecimal conversion. I think there are desktop calculators allowed on exams that provide similar functionality, if you don’t happen to have a TI-89. Come to think of it, the exams weren’t particularly rushed, so there would’ve been plenty of time to conduct these conversions by hand.

Extra Resources

Difficulty and Time Commitment

Of all the classes I’ve taken in this program (161, 162, 225, 261, 271, 290, 325, 340, 361, 372, and 475), I’d say this is in the upper end of difficulty, but definitely not at the top. Not so much because of the conceptual challenge, but because it’s a bit of a slog. The work is well-spaced out, which means that I never felt like I was getting ahead. There’s always another lab, or summary exercise, or project. That makes starting early particularly important. On the positive side, the course is clear and well-organized, so most of the struggle is with the material itself. There’s nothing worse than trying to figure out the course when you should really be trying to figure out the material.

I spent about 70 hours on this course, which works out to about 7 hours per week. To put that in perspective, I spent 12 hours per week on Algorithms, 9 hours per week on Databases, and 9 hours per week on Web Development.

For what it’s worth, I took two other courses this term (Parallel Programming at Oregon State and Calculus IV at Portland Community College). I also take care of my daughter (along with my wife and in-laws).

Enjoyment

This was a good class. The original designer Paul Paulson and the current instructor Stephen Redfield really seem to care about pedagogy and learning outcomes. If I remember correctly, this is the same designer/instructor dream team who brought you Assembly (271), so if you liked that class I’d expect that you’d like this one, too.

I remember coming away from Assembly in awe of how the movement of bits and bytes came together into a functioning machine. This course on networks imparts a similar appreciation, except instead of just one machine it’s billions, the world over, all sending and receiving at once.