Rachael, me, and Idara in the desert near Zekreet.

Rachael, me, and Idara in the desert near Zekreet.

Whenever someone would ask Rachael when we were going to have kids, she’d say that we’d have to decide on a name. A last name, that is.

The subtle message was to mind your own business, but Rachael was also keen to point out that just like having kids, last names shouldn’t be taken for granted.

We have different last names, so the question of what to do with a child’s last name was an open one. Rachael wanted it to have her last name, and I wanted to it have mine. We both had our reasons.

I wanted everyone to know it was mine, from casual acquaintances to border control agents who might someday question why I was traveling with a child who didn’t share my last name. Nowadays, no one gives a second thought to a woman and child with different last names. But I thought it would be a different story for a father.

I was also worried what people would think, especially my parents and grandparents. How would they take to their grandchild not being given the family name? Beyond my family, I was worried about being the butt of a lifelong joke. I doubt anyone would ever say it out loud, but I’m sure that people would think me weak, or whipped, or that I no longer wore the pants in the relationship. And how could I blame them? I know that’s what I’d think.

Rachael’s arguments were more straightforward. She’s the last Molitor in her family, so the name would die with her unless she passed it on. And on top of that, she said that it was unfair that a child automatically be given the father’s last name. I agreed that it was unfair for it to happen automatically. I wanted it to be a discussion, too, just one that I won in the end.

So we argued, off and on, for years. Rachael and I hadn’t even decided to have kids, but somehow we mustered the energy for regular knock down drag out last name fights.

When we found out last year that Rachael was pregnant, what was once a philosophical argument became much more concrete. Assuming neither of us gave in, we had three options for picking a last name that we decided were fair: combining our names into one, hyphenation, and a coin flip.

It didn’t take long to toss the name compilation choice out the window. Would our child be a Molison? A Johnsitor? A Molijohnsitorison? No thanks.

Hyphenation definitely has some strengths. For one, it’s about as equal a naming scheme as you can get, except that one name has to go first. But it also sounded long and complicated. And what happens if your child has kids and has to choose their last names? They’d either have to keep tacking on last names or choose which ones stay and which ones go. Then you’re back to square one, or at least your children are.

That left the coin flip. It definitely had a fairness to it, and it prevented either person from trying to sway the other. You just flip a coin and it’s done. The downside of the coin flip, though, is that someone has to lose. And when we gave up on the other options and decided to flip a coin to decide our unborn child’s last name, that person was me.

Only a few minutes passed before Rachael decided that she didn’t want to win by coin flip, but it was the closest we’d gotten to a decision and I wasn’t about to throw it away. It may not have been the result that I’d been hoping for, but at least it was a result, rather than a protracted argument.

For a few months, we left it at that. But then a web comment caught my eye:

We should try…daughters taking the mother’s surname and sons taking the father’s. My husband and I did that and there has never been the slightest problem with different last names.

I immediately loved the idea. It was like a coin flip because we both had an equal chance of having our last name chosen. And if you had a boy who took the father’s last name, you could use the mother’s as the middle name, which I realized after the fact is exactly what my parents had done with me. It’s a nice consolation, I think, and would tie the child to both parents and both sides of the family.

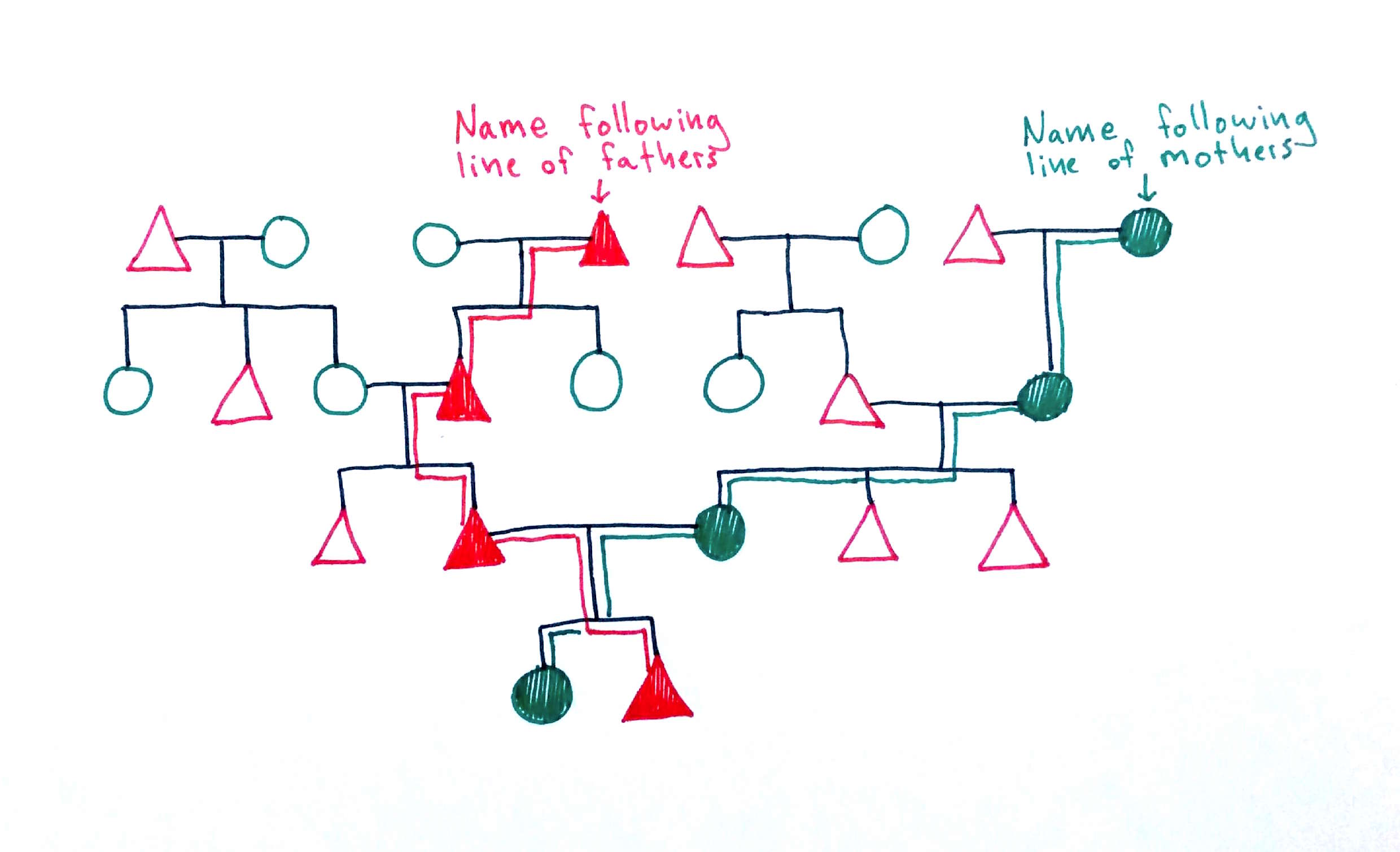

There were other strengths, too. If you carried this naming scheme on continuously, not only would you be able to trace the male line of a family tree forever, you’d be able to trace the female line that way, too. And all of this without hyphens, or a dozen last names, or just pretending that one of the parents didn’t have a role in the child’s creation. You’d give up choosing your own middle name, but I think that’s a small price to pay for this kind of genealogical and nominal symmetry. And if each one of these strengths weren’t enough, it turns out that it’s actually the sperm that determines the child’s sex. Even if there was a 50 percent chance that I wouldn’t get what I’d hoped for, I could still have a laugh, though maybe not the last one.

Red for the patrilineal name, green for the matrilineal name. If you really want to nerd out, though, think about just tying the child’s last name to the Y chromosome. No Y chromosome because you had a girl? Then just use the mitochondrial DNA! Easy!

Red for the patrilineal name, green for the matrilineal name. If you really want to nerd out, though, think about just tying the child’s last name to the Y chromosome. No Y chromosome because you had a girl? Then just use the mitochondrial DNA! Easy!

Now that I’d convinced myself, it was time to sell Rachael on the idea. If she’d wanted to, she could’ve just gone back to the coin flip which she’d won, but she didn’t. She didn’t want there to be a winner and a loser, either, and I think my enthusiasm for a naming scheme that might not work out in my favor was all the convincing she needed.

I’d gotten so caught up in how perfect this naming scheme was that I’d forgotten that it didn’t really do much to allay the fears I had about having a different last name than my child. Chief among them, as I wrote before, was what people would think. It’s easy to say, “Who gives a damn what people think?” It’s harder when you love and respect those people, and genuinely do care what they think.

I started to feel things out, but to my surprise, no one in my family seemed to care. Some of them even thought it was a cool idea. Maybe they were secretly judging us, but if no one felt strongly enough to say anything about it, then I wasn’t going to worry about it. I’d still have to worry about what other people thought, but only if we had a girl. Which, of course, we did.

There’s a line in an essay by Mary Schmich which goes: “Don’t worry about the future…The real troubles in your life are apt to be things that never crossed your worried mind, the kind that blindside you at 4 p.m. on some idle Tuesday.” When Idara blindsided us on a not-so-idle Wednesday, I quickly realized how inconsequential all of my previous worries were. She was tiny and helpless and covered in amniotic fluid and perfect. I was in love and could think of nothing besides her well-being. Rachael could’ve named her Booger and I’d have been no less smitten.

In the minutes after Idara was born, I looked at Rachael and said, “You know what this means, right? Your last name?” She said that we could use mine if I wanted to. Imagine that: years of fighting over this only to be tripping over each other to concede. Nothing like the afterglow of childbirth to make you forget yourself. But I didn’t want her to concede. We’d made a plan and I wanted to stick with it. And anyway, weren’t there more important things to think about? Wasn’t there a baby who needed holding?

It’s been four months since Idara’s birth, and I’ve yet to have a single person mention the fact that she and I have different last names. If that’s any indication, then I’m sure Rachael and I will have spent more time talking and worrying about this than anyone else. But I won’t say it was wasted time. Names are a big deal, and I’m glad we’d thought about it as much as we did.

When I first imagined writing this post I thought it’d be an explanation of an odd decision, like I had to pull someone aside and say: “OK, but hear me out…” No. It’s not. This is no confession, no concession, no explanation. Rather than being embarrassed about having a different last name than Idara, I’m proud. Proud that we didn’t bend to popular opinion, proud that we didn’t just do things because that’s how they’ve always been done. And as Henry Ford, or Tony Robbins, or maybe just someone on the internet said: “If you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you’ve always got.” Maybe it’s time we got something different.

I know Idara won’t care. Or perhaps there will be a decade or two when she’ll be the one who’s embarrassed. “Why’d I have to have such hippies for parents?” she’ll probably wonder. After a while, though, maybe she’ll see where we were coming from.