A few weeks back I had coffee with Chris Bartlo, a computer science teacher at Wilson High School. He said that when one of his students is learning a new programming language he counsels them to use it to write tic-tac-toe. The rules of the game are simple and don’t change from language to language, so creating the game makes for a good exercise in loops, input validation, and other language features.

After finishing a course on Assembly (MASM, specifically) this summer at Oregon State, I decided to put Chris’s advice to use and write tic-tac-toe in Assembly.

Sharing the Work

Before I’d started on the project I had (what seemed like) a brilliant idea. Why not ask other students in the class if they’d like to participate? We could break out the project into a few different parts and then share our code via a git repository. I invited others to take part but soon realized that writing tic-tac-toe in Assembly is not exactly the kind of side project that would get people excited. Maybe if I solicited help writing a web server instead? Or maybe a Photoshop clone?

After I finished the project and shared it with other students via Slack, someone posted this meme. Not far off!

After I finished the project and shared it with other students via Slack, someone posted this meme. Not far off!

Seriously, though, I’ll definitely keep inviting people to work with me on these side projects. Group work in classes always feels forced, but maybe working together on something outside of class won’t, and might provide some valuable experience.

Solving Problems

I began by putting pencil to paper and trying to imagine what procedures I’d need to complete the program. I can’t say emphasize enough how much more helpful it is to start with paper when programming. This isn’t a new idea, of course, but it was front-of-mind for me because I’d recently finished rereading “Steal Like an Artist” by Austin Kleon. If you haven’t read it, do!

The procedures I settled on implementing were:

- printIntro

- clearBoard

- printBoard

- chooseSquare

- checkWinner

- processWinner

- processCats

- switchPlayer

- printOutro

Some of these might’ve been more easily implemented as macros, but I wanted to practice writing procedures. I also wanted to practice passing parameters on the system stack. The only variables in the program that weren’t passed on the stack were strings.

The first problem I knew I’d encounter was how to allow a user to choose a square in which to place an X or an O. As I was writing this as a command-line game, there would be no pointing and clicking with a cursor. I settled on numbering each square, 1 through 9. That way the user could just look at the board and input a number in order to select their square. This also facilitated error checking — all I had to do was see if a number was between 1 and 9.

But what should the board be? I decided to make it an array of bytes with line feeds and carriage returns to form new lines. This allowed specific bytes to correspond to specific squares on the board. For example, square 1 corresponds to byte 30, square 2 corresponds to byte 38, and so on. This gave me specific locations to place X’s and O’s and also to check for runs (three consecutive X’s or O’s).

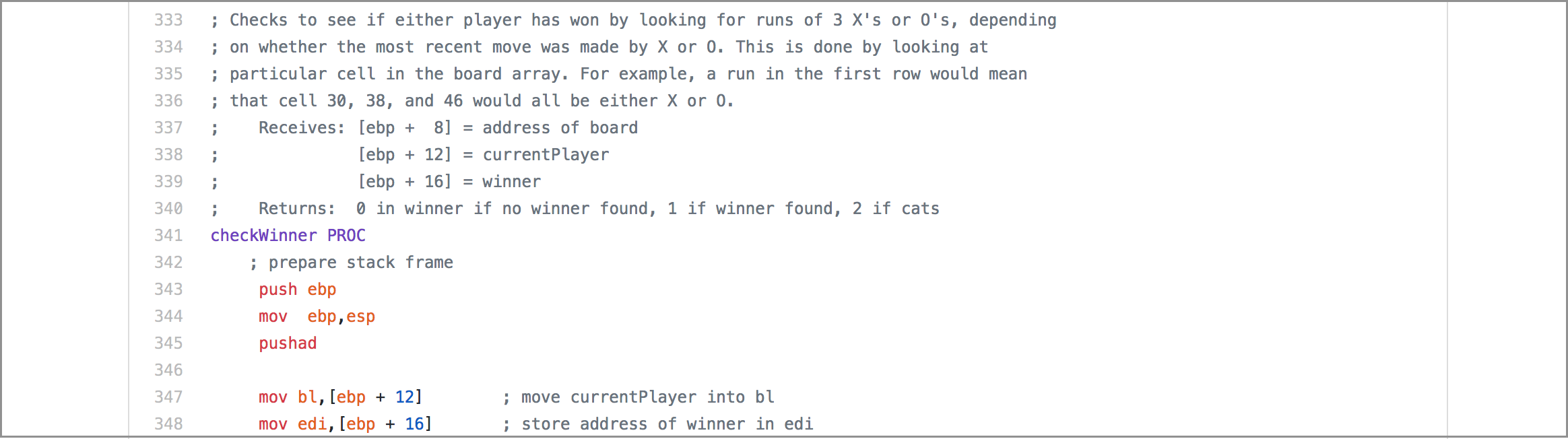

Here’s what the board ended up looking like:

Welcome to TicTacToessembly!

1 |2 |3

| |

| |

-------+-------+-------

4 |5 |6

| |

| |

-------+-------+-------

7 |8 |9

| |

| |

Wrapping Up

The entire program is just under 700 lines long. There were a few parts where duplicating code was more straightforward than increased customization, so I suppose it would’ve been possible to shorten it.

There was a period of time after I’d finished sketching out the design and before I’d started coding when I thought, ‘Ugh, this is going to take forever.’ I was pleasantly surprised that I was able to finish it in just a few days working a couple of hours a day.

You can see the final code for the program here.