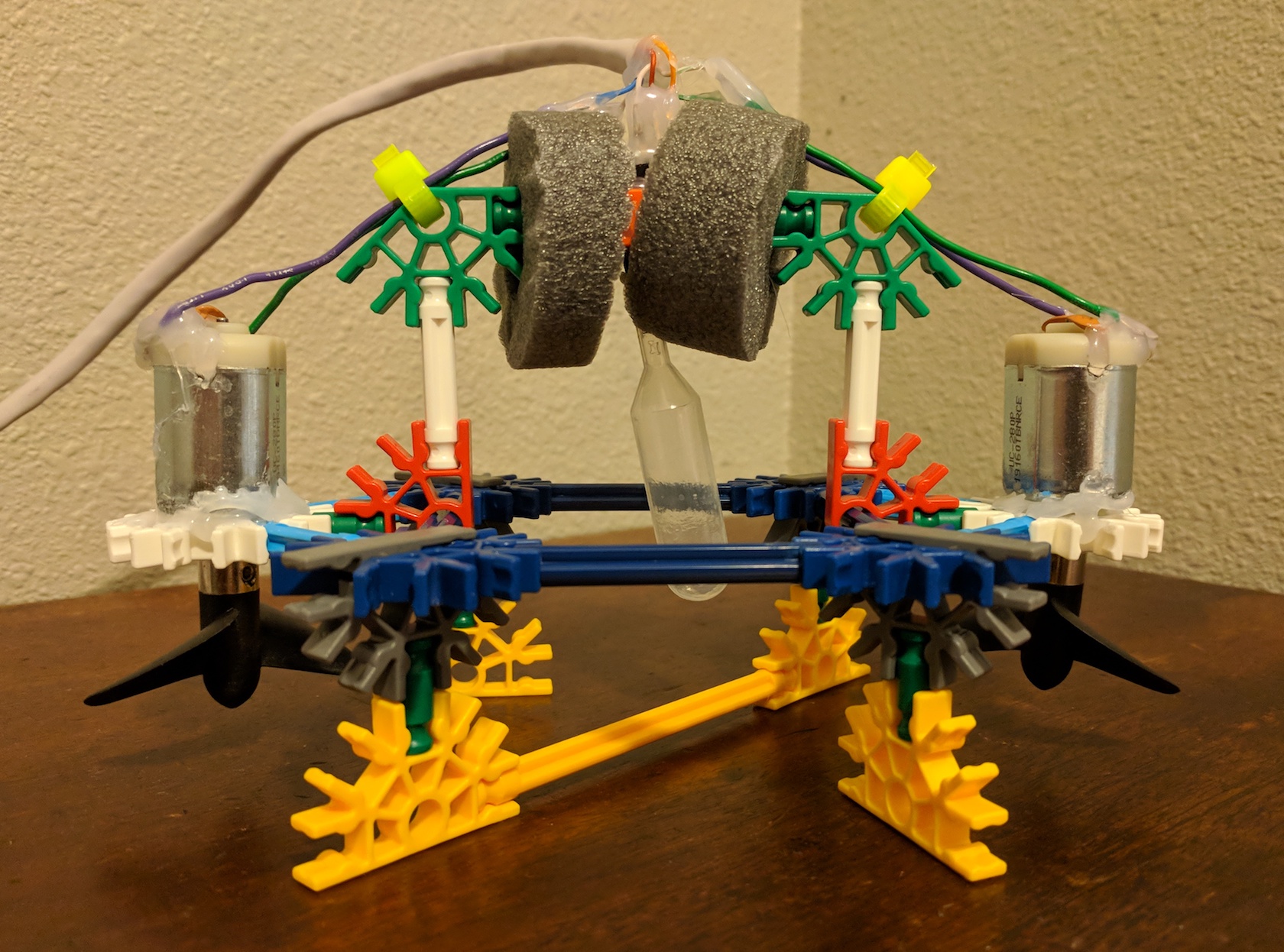

The submersible ROV I built as part of SuperQuest in The Dalles. The pressure sensor is in the middle and controls the movement of the motors on the sides.

The submersible ROV I built as part of SuperQuest in The Dalles. The pressure sensor is in the middle and controls the movement of the motors on the sides.

On Monday and Tuesday of last week, I skipped work to attend a SuperQuest conference in The Dalles. It was organized by the Oregon Computer Science Teacher’s Association, which also organizes other similar conferences around the state along with a yearly statewide conference in October. I haven’t been to that one yet, but I’m planning on going this year.

I decided to attend the conference for a few reasons. One, I wanted to get a feel for how computer science is being taught in Oregon and by whom. Two, I wanted to make connections that might be valuable in the future. And three, I wanted to further develop my sense for whether education or industry is a better direction for me. I’m pretty confident that I’m on the right track with my plans to teach, but it never hurts to have more information.

Each day of the conference had a similar structure. There was a morning session and an afternoon session, divided by a provided lunch a short talk on a particular subject.

The class I’d signed up for was called “Arduinos and Programming in the STEM Classroom.” I have a bit of experience with Arduino, thanks to the dust sensor project I ran when I was in Doha, but I’ve never used them in a classroom before and wanted to see how they could be used as a teaching tool. This is especially prescient for me right now because I’m planning on teaching a mini-lesson on physical computing at Wilson High School, where I volunteered last year and will be volunteering again this year.

The class was run by Greg Mulder and Heather Hill, both physics instructors from Linn-Benton Community College. Greg also leads the ROV Team at Linn-Benton, and his experiences with that served as the foundation for what he was teaching at SuperQuest. My group had about eight participants, including a speech therapist, an integrated sciences teacher, a woman who worked for OCDC, another woman who worked for 4H, an AmeriCorps volunteer, a high school student, and a couple other people whose jobs I can’t remember.

I was expecting a more techy group, but even so, it was a pleasant surprise. And it made sense in light of something I heard during the lunchtime lecture later in the day: there just aren’t a lot of people with computer science degrees going into education, so the powers that be are trying to make up that gap by training existing teachers in computer science and programming rather than training computer scientists to teach. Even as someone who’s basically doing the latter, I think the former is probably much easier.

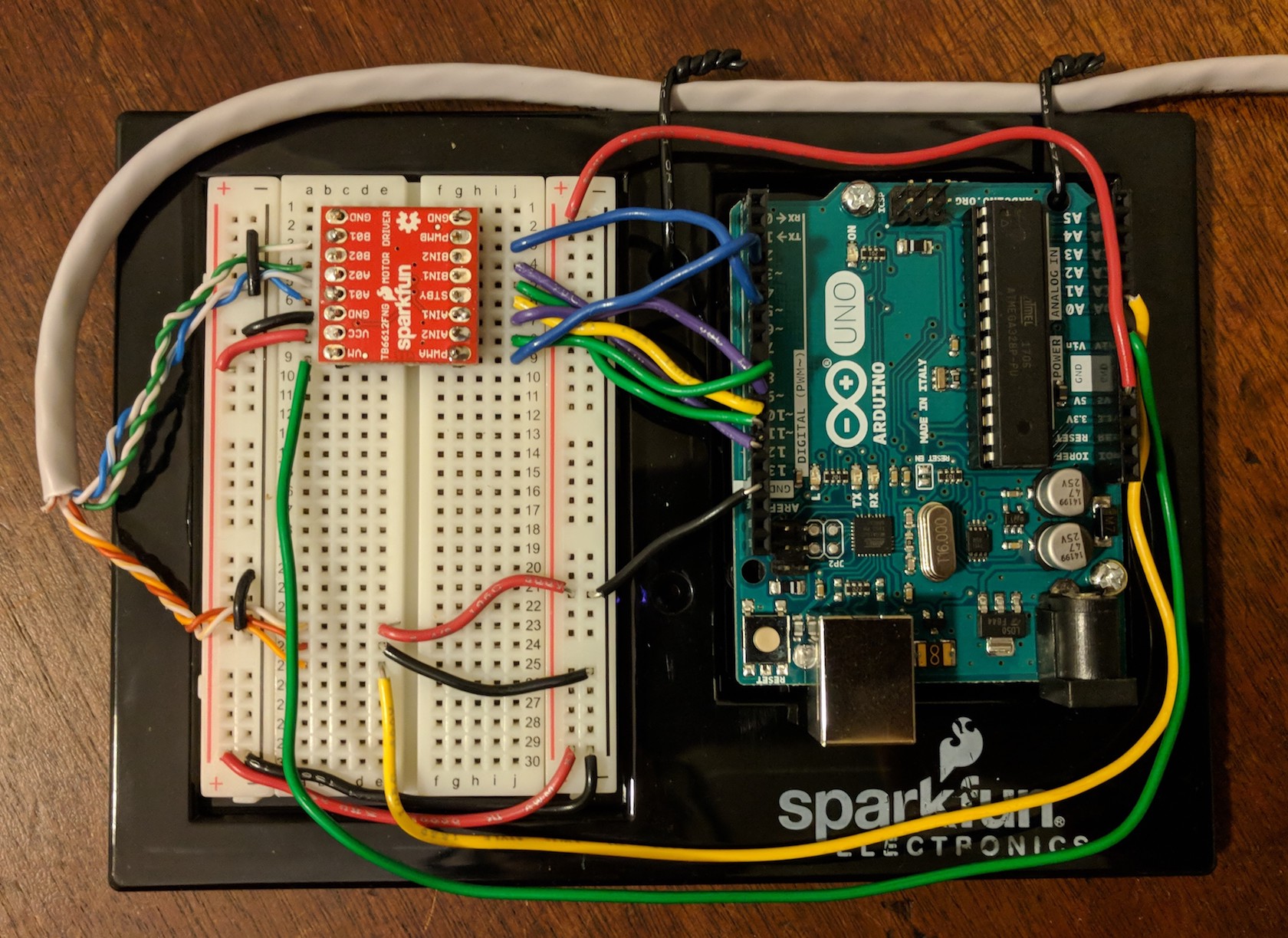

The class itself was pretty simple. We were lightly guided through a series of lessons, starting with making an LED blink (the Arduino equivalent of “Hello World”), then adding a light sensor, then a pressure sensor, and finally running motors through a motor driver. All of this was then combined into the final goal of the class: making a submersible ROV and testing it out at a local pool.

The Arduino and bread board that I used to power my submersible ROV. The red chip in the middle is a motor driver from SparkFun.

The Arduino and bread board that I used to power my submersible ROV. The red chip in the middle is a motor driver from SparkFun.

My favorite part of the course was that less and less guidance was provided at each step. For example, example code was only given for the first few steps, then it was up to the student to combine what they’d already learned and fill in the gaps by asking questions and searching online. The final stage, “build an ROV” provided almost no direction at all.

From my perspective, this strategy served two goals: First, it provided more instruction at the beginning, where it’s needed most. And second, it allowed for more creativity toward the end, where it’s most likely to be taken advantage of.

Providing more direction at the beginning and less at the end seems like the most basic common sense, and it is, but it’s a good reminder, too. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that it’s necessary to hold students’ hands the entire way, or alternatively, to believe that it’s best to just throw students into the deep end. As with all things, balance is the key.

Another valuable reminder that I gained from the class was to always let the students do the doing. On one occasion I saw one of the instructors doing something for a student instead of letting them do it themselves. As I found during my time at Wilson High School last year, this is an easy thing to do. A student is struggling with a problem, and I feel like I understand it well enough to do myself, but not necessarily well enough to explain. Either that or I’m just trying to save the student from any unnecessary feelings of frustration. So I ask if I can sit down and bang it out myself. This might get the problem solved, but it prevents the student from learning anything in the process. Even worse, it robs the student of any sense of satisfaction and ownership at having solved the problem on their own (or at least mostly on their own). This is one of the greatest motivators that exists in learning computer science, and I should think twice before taking it away from my students.

Toward the end of the second day our classroom was a mess. There were computers and wires and chips scattered all over. There was a water bucket that we were using for testing and a station set up for soldering and glue guns. The other SuperQuest sessions, by contrast, looked antiseptic. It may just be my bias, but none of them looked nearly as fun as ours. I suppose tools like Code.org (the topic of another SuperQuest session) have their place, and it’s true that most programming and computer science jobs don’t involve soldering and designing circuits, but doing what we were doing is definitely more fun. And at least for me, that’s the main draw.

After we’d built and tested our ROVs we took them over to a local pool and dunked them in the water to see how they fared. I’d designed mine to turn on it’s motors once it reached a certain depth (as measured by an onboard pressure sensor), and it did just that. Everyone else’s worked too, and thanks to the creativity afforded by the curriculum, they all worked in slightly different ways.