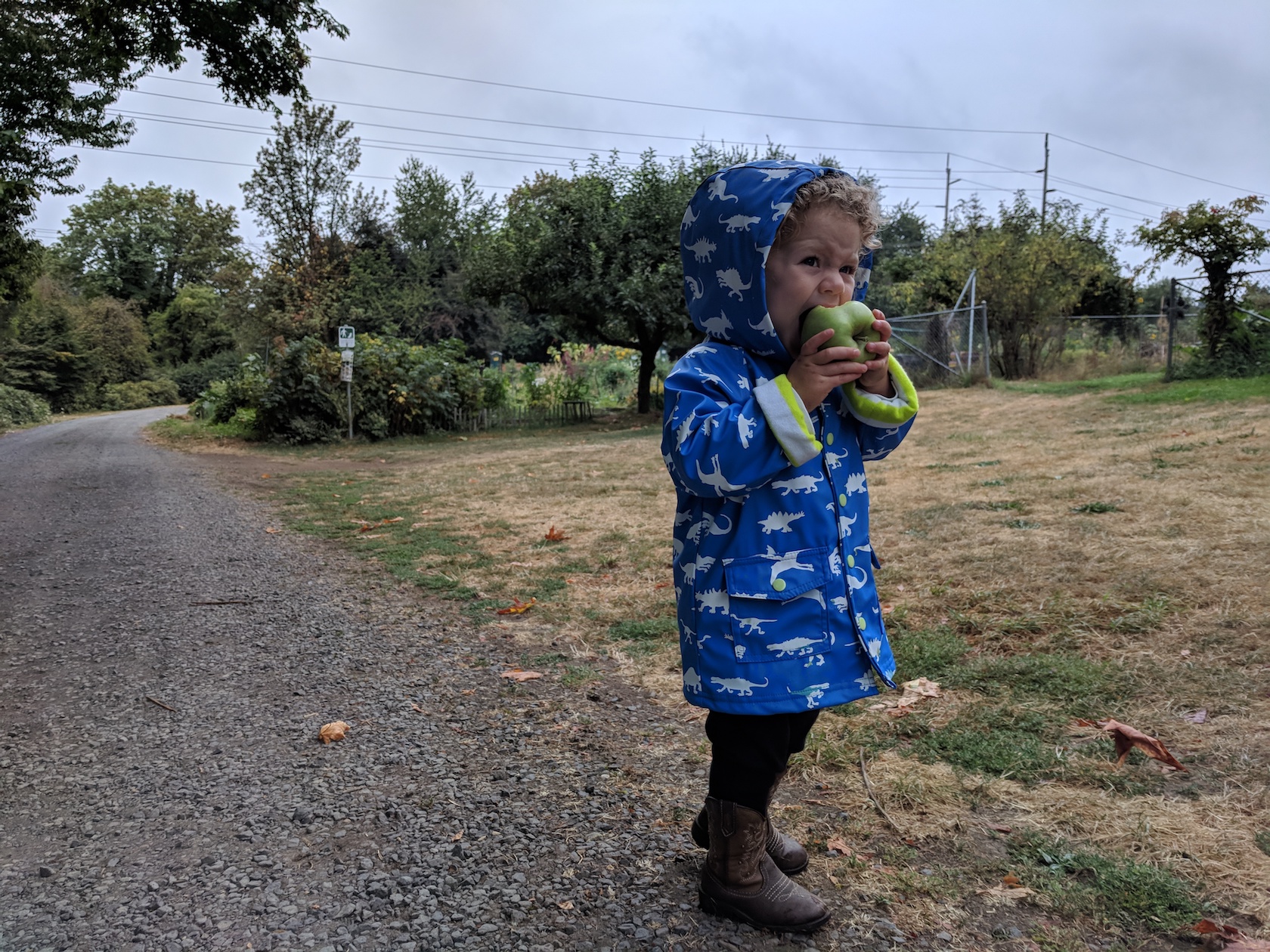

Idara sampling an apple from one of the trees at the community garden.

Idara sampling an apple from one of the trees at the community garden.

I recently finished one of the most thought-provoking books I’ve read in the past few years. I often write down notes after I finish a book. Rather than keep them to myself, though, I think it would be nice to share them here. This book seems like a good place to start.

The Big Idea

The central theme of the book is that children today suffer from a lack of exposure to and participation in nature, loosely defined.

The author, Richard Louv, describes a variety of causes, including over-reliance on technology1, a lack of space, overly-protective parents, and an overly-litigous society.

Before I committed to the book, I was skeptical of one thing in particular. Anyone who talks about “kids these days” is almost certainly romanticizing their own childhood. Were the 1950’s really that great? There was still polio.

To his credit, Louv addresses this romanticism directly, and concedes that he may have an unrealistically positive view of his own childhood in Kansas.

Even so, it’d be hard to look around and think that kids are better off spending more time inside or having less time for recess. That’s the beauty of the book, really. The case he’s making is completely self-evident, but sometimes I need someone to point out something that’s staring me right in the face.

Observation versus Experience

One of the critical distinctions Louv makes is between observing nature (by taking a hike along prescribed trails, for example) and experiencing nature (by building a tree fort, or damming a creek, or hunting, or fishing).

The hunting and fishing part were particularly interesting to me, since they’re often imagined to be the opposite of environmentalism. But this need not be the case, neither in theory nor in practice. For example, Ducks Unlimited, an organization made up almost entirely of hunters, has protected millions of acres of wetlands. It’s hard to imagine the same conservation outcomes if hunting were no longer an option. But I digress.

It’s easy enough to say, “Kids should play outside more.” But what does that actually look like? It almost goes without saying, but taking kids on a hike and telling them they can’t so much as pick a flower doesn’t really instill a relationship with nature.

This runs counter to a modern environmental orthodoxy. What would happen if everyone picked a flower? Louv defends his position by claiming that someone who actively participated in nature as a child is more likely to defend it as an adult.

I think he’s right. Lord knows how many sapplings I hacked up when I was little, or frogs I condemned to an early demise in a jar on bookshelf. But I’m certainly a more ardent defender of trees and frogs now.

What to Do?

Rachael read this book before me and told me about it as she progressed. As she read about symptoms of the problem in the first half of the book, I kept asking her, “But what do you do about it?” It’s easy enough to point out that we have a problem. Solving it is something else entirely.

Louv’s prescription spans the second half of the book and involves everything from technology, to local and national politics, to tort reform. The upshot, though, is this: put kids where magic is possible and then take a step back to let it happen.

At Idara’s age, this is easy enough. She knows how to open the door to the backyard and can go explore whenever she wants. There’s grass and dirt and rocks and plants and bees back there, and she’s just beginning to discover the wonders of spraying a hose.

I also bring her along to my community garden plot and let her wander around while I work. I used to tell her not to pick things out of other people’s gardens, but after reading this book I’ve changed my mind. Sampling tomatoes and raspberries right off the vine is one of the great joys of gardening, so I think it’s OK if she annoys some people in the process. And anyway, everyone else seems to be a better gardener than me, so it’s only fair that she helps balance things out.

Criticism

The main criticism I had of the book was that it was just about kids and nature, as if I could improve a Idara’s relationship with nature without improving my own. On the other hand, if I dislike the outdoors, Idara seems all but certain to adopt my attitude.

I’m sure Louv agrees, and I can appreciate that he framed the book the way he did. It just would’ve been nice if he’d addressed this idea more directly.

-

The book was published in 2005. Imagine what he’d say about technology now. ↩