In June I started classes at Lewis & Clark’s Graduate School of Education, where I’m working toward a Master’s of Arts in Teaching. Now, after completing six courses in two months, I finally feel like I have a moment to come up for air and write a little bit about my experiences.

This summer I took six classes:

- Writing and the Writing Process (LA 531)

- Social, Historical, and Ethical Perspectives on Education (ED 550)

- Culturally Responsive Teaching (ESOL 540)

- Adolescent Development (ED 552)

- Probability and Statistics (MATH 502)

- Algebra for All (MATH 527)

I have a little bit to say about each of these courses. There’s some overlap, though, so I’ve grouped some of them together. In the interest of brevity, I’ll refer to the course entitled Social, Historical, and Ethical Perspectives on Education as the policy class, since that’s mostly what it was about.

Writers’ Workshop

The program began with a three-day writers’ workshop. There are about forty secondary “teacher candidates” in total, and we were split into two groups of approximately twenty students each. My group was led by Laura Moulton, an adjunct professor at Lewis & Clark and the founder of Street Books, “a bicycle-powered mobile library that serves people who live outside.” The other group was led by Kim Stafford, who leads the Northwest Writing Institute and was recently named Oregon’s Poet Laureate.

I must admit some initial disappointment at not having the opportunity to work with Kim, but my disappointment quickly faded. Getting to see Laura lead a writers’ group was a treat in and of itself, and I found myself wondering when I might have the opportunity to work with her again.

The class itself was simple: read, write, repeat. We read poems and essays written by others, wrote our own lines, and then read them aloud to the rest of the class.

On our second day we were set free for a couple hours to write our own essays. Inspired by the intimacy that our group had created with Laura, I wrote about something I’d literally never shared with anyone, and I think it’s one of the best things I’ve ever written. I’m still trying to figure out the right venue for it, whether this blog or somewhere else, but for now it’s a shared secret with that one-time writers’ group.

Why start a graduate program with a writers’ workshop? I don’t know what the intention was, but I know that for me the experience was transformative, almost religious, and it reminded me of the power of writing to draw strangers together and to bring me closer to my true self.

Social Justice I, II, and III

When I was deciding whether to attend Lewis & Clark, an administrator told me that the thing that sets it apart from other schools in the area is its focus on social justice. A few weeks later an admissions counselor at Portland State told me that what sets them apart was…their focus on social justice. Ha.

I can’t speak to whether Portland State makes good on this claim, but Lewis & Clark certainly does. In fact, I joked that the courses on culturally responsive teaching, adolescent development, and policy could be renamed Social Justice I, Social Justice II, and Social Justice III.

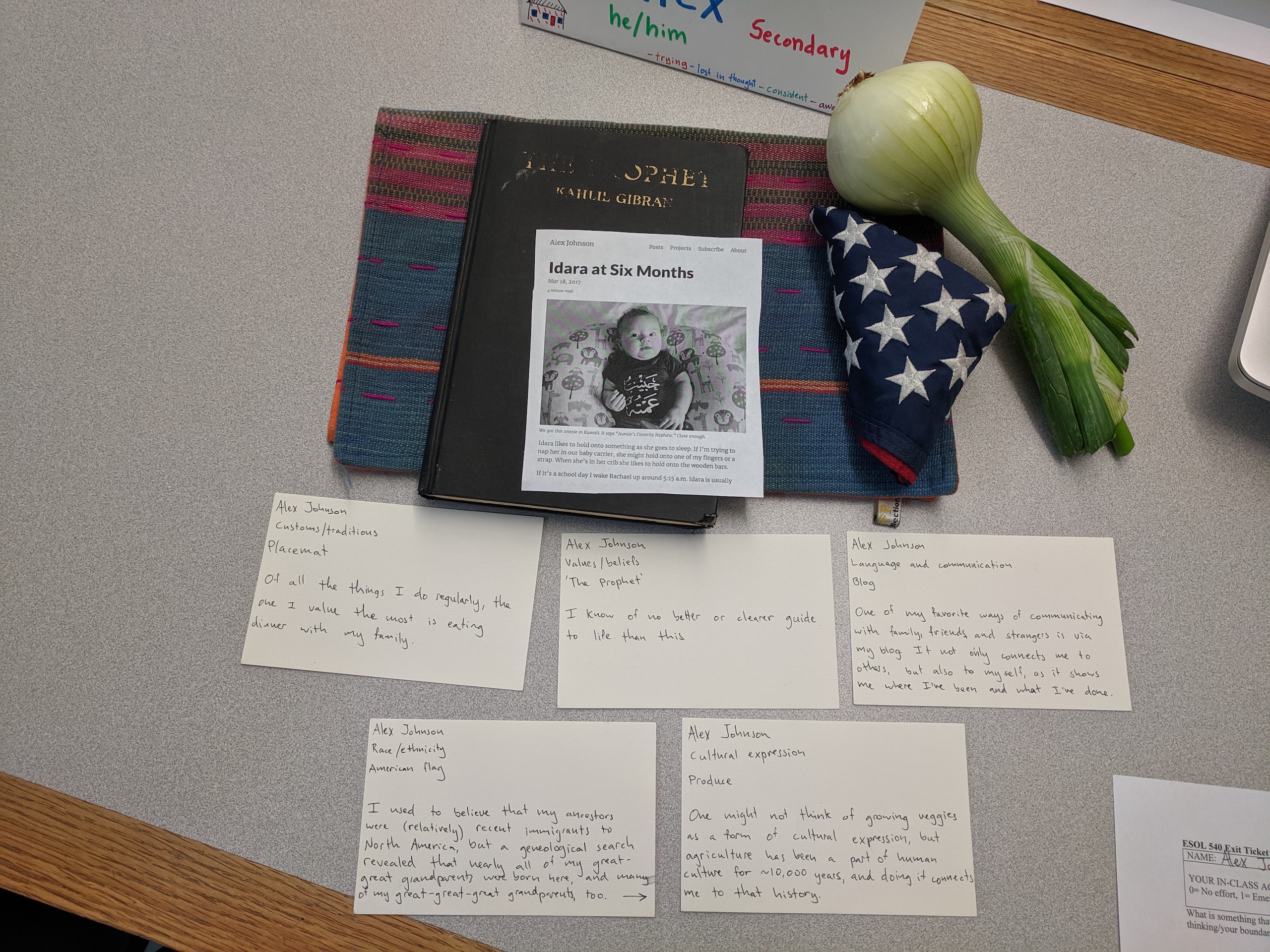

One of my favorite activities from this term, and one I’d like to duplicate with my own students, was a bit like show and tell. Each of us brought in a few items that described us as individuals and then presented them to the rest of the class. Everyone loves talking about themselves, but even better is to hear about what other people brought in and why those items are significant to them.

One of my favorite activities from this term, and one I’d like to duplicate with my own students, was a bit like show and tell. Each of us brought in a few items that described us as individuals and then presented them to the rest of the class. Everyone loves talking about themselves, but even better is to hear about what other people brought in and why those items are significant to them.

I wondered whether we would ever talk about anything else. Now, don’t get me wrong. I’m not skeptical of the aims of social justice (and if you are, you might want to ask yourself why), I just didn’t want to miss out on the other parts of effective teaching, like classroom management, lesson planning, and so on.

What I came to understand, however, is that social justice is not a facet of education, it’s part of the foundation. So it makes sense to cover it in detail, from multiple perspectives, and from the very beginning.

Kids do well when they can

The overarching theme of these courses, from a practical perspective, is that “kids do well when they can.” In other words, if we as educators can craft an environment that is conducive to student success, then our students will succeed. This is in direct opposition to the idea that students must develop “grit” in order to overcome a subpar educational system. Better to just improve the system.

Granted, this is a false dichotomy. It’s possible to build an environment where a student is more likely to succeed and help them develop self-reliance. But if a teacher says that the responsibility of learning is solely on the student, what exactly are they teaching? And how?

Education debt

Another thing that stuck with me is Gloria Ladson-Billings’ concept, expressed in this address, of “education deficit” versus “education debt.” In a nutshell, the idea here is that some groups have been operating at an education deficit for generations. They’ve had less access and had fewer resources. So even if we make sure that all students receive equitable access and resources this year, we’re still carrying along a long history of inequity. In other words, just because I made my rent payment this month doesn’t make up for all the previous months when I didn’t. And if you think that American education has been equitable from the beginning, or that we’ve made up for that discrepancy, then I’d like to know why. Email me.

Public goods and private goods

Another idea, from the historian David Labaree, is that education in America serves three primary purposes: democratic equality (educating citizens to govern a democracy), economic efficiency (providing intellectual capital for the economy), and social mobility (allowing individuals to climb the social ladder through educational attainment). None of these is better or more important than the others, but we run into problems, Labaree argues, when they get out of balance. This brings me to my final point, below.

A Nation at Risk(?)

One of the presentations I had to give for policy class was on the state of public education in America from 1980 to the present. One of the central events in this period was a report entitled “A Nation at Risk.” The report, which was commissioned by the Reagan administration, painted a dire picture of our educational system based on declining test scores. A few years later another report completed at the Sandia National Laboratory found that while test scores in aggregate were declining, they were actually increasing for individual subgroups (see Simpson’s paradox). But by then it was too late. “A Nation at Risk” had dramatically shifted narrative and policy toward education as a private good used primarily for social mobility, and its effects can be seen to this day.

Probability, Statistics, and Algebra

I took two content area courses in addition to the courses described above. The first of these courses focused on probability and statistics and the second course was on algebra.

Rather than the content, though, the course was centered on teaching the content. For example, what sort of activities will help students develop intuition about how mean, median, and mode influence a histogram? Or a box and whisker chart? What sort of misconceptions related to compound probability can we dispel? And so on.

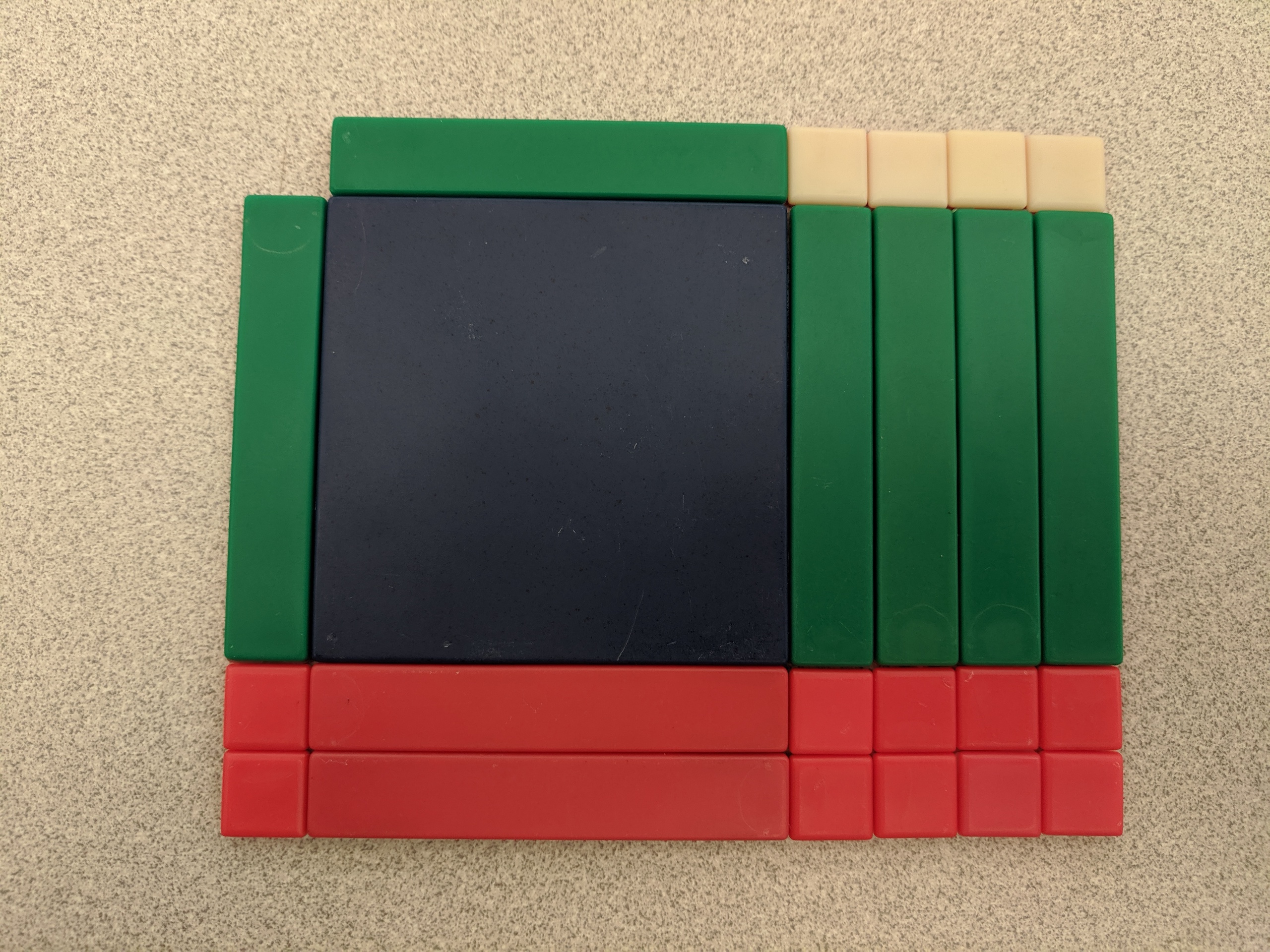

These are algebra tiles. The small squares represent units, the bars represent a variable like x, and the large square represents x². A red tile of any of those shapes represents a negative value. This particular arrangement shows that (x+4)(x-2) = x² + 2x - 8. The top shows x+4, the left shows x-2, and the rest of the shapes show their product.

These are algebra tiles. The small squares represent units, the bars represent a variable like x, and the large square represents x². A red tile of any of those shapes represents a negative value. This particular arrangement shows that (x+4)(x-2) = x² + 2x - 8. The top shows x+4, the left shows x-2, and the rest of the shapes show their product.

I enjoyed these classes, especially since they usually offered a respite from the depressing conversations about systemic racism and other social injustices that took place in our other classes. Not that those subjects aren’t important, it’s just nice to have a break.

Lesson planning

One of my favorite activities came at the end of the algebra course, when we were tasked with preparing a lesson plan and carrying it out with the other students in the class.

I chose to present an introduction to irrational numbers. Examples you’ve probably come across are π, e, and √2. I thought that this would be a straightforward topic, but I was wrong.

The definition of an irrational number is simple enough. It’s just a number which cannot be expressed as the ratio of two integers. The implications, however, are anything but.

Take the right triangle with two legs of length 1. You might remember from your geometry or trigonometry classes that its hypotenuse has length √2. The legs of length 1 have precise decimal representations: 1.0. But the hypotenuse does not. Its decimal representation starts with 1.41421 and continues endlessly without pattern or repetition. Weirder still, if you were asked to place this value in its correct, exact position on a number line, you couldn’t do it. There will always be some “more exact” value that might shift its position to the left or right.

I had this pretty well worked out in my mind, along with a nice introduction about the Greek mathematician who was supposedly put to death for claiming that irrational numbers exist. A few minutes in, however, my presentation began to fall apart. I knew it in my head, but I didn’t know how to get it from my head to anybody else’s. Just talking about it wasn’t enough.

As a lesson, it was a minor failure. But it was a success in that I found it a very inspiring failure. I wanted to perfect this idea, and figure out exactly how to communicate it. And I think that’s where I’m headed.

Overlap

Since Lewis & Clark is a year-long intensive program, there’s no overlap between students who are veterans in the program and complete newbies. That is, unless you’ll be teaching math. We take an extra class at the end of the program, which means that this summer we overlapped with a few students who were about to graduate. I’ll do the same next summer.

One day as I was walking out of class I asked one of these students a quick question which then grew into a long conversation about the program, what I should focus on, and what I should watch out for. Her advice was to invest as much of my energy into my student teaching as I possibly could. Everything else, she said, should come second.

Onward

In a couple weeks I’ll begin my year of student teaching at Wilson High School. I’ll also start a new round of classes at Lewis & Clark. And come early September, assuming all goes to plan, our family will grow by a third. Here we go!