Last weekend I went to Code Retreat, a hackathon-esque gathering centered around a simple idea: building Conway’s Game of Life in teams with a variety of constraints imposed on the programming process. I decided to go for two reasons: First, to meet other programmers, and second, to gain some experience coding with strangers. By the end, I’d found that participating in the hackathon was an excellent way to test my skills and show me what still needed further development. Hence the title of this post, Hackathons as Test-Driven Development.

The event took place in the Portland offices of Slalom Consulting on the 25th floor of Fox Tower. There were about 30 of us in all. It started at 8 a.m. and went until around 5 p.m. The event was free, including a catered lunch.

After a brief introduction from Matt Plavcan, the organizer, we were set loose with out laptops to build Conway’s Game of Life — in 45 minutes. It seemed an impossible feat, and it turns out that it was. There was no expectation that we’d reach the goal, only to work toward it. So that’s what Tim, a recent computer science grad from Portland State, and I did.

He sat at his laptop and coded in Java while I drew diagrams and wrote pseudocode on a whiteboard. Our first instinct was to represent the game board as a two-dimensional array of ones and zeroes. Then came a review of the rules and a brief conversation about how they might be implemented. And then the time was up.

Test: Can I implement an idea under a time constraint?

Development: Practice coding with a time constraint.

The group reconvened and discussed what worked and what didn’t. A few people talked a lot and most everyone else was quiet. I found myself too intimidated in the beginning to say anything, especially since I appeared to be the only non-professional programmer in the group.

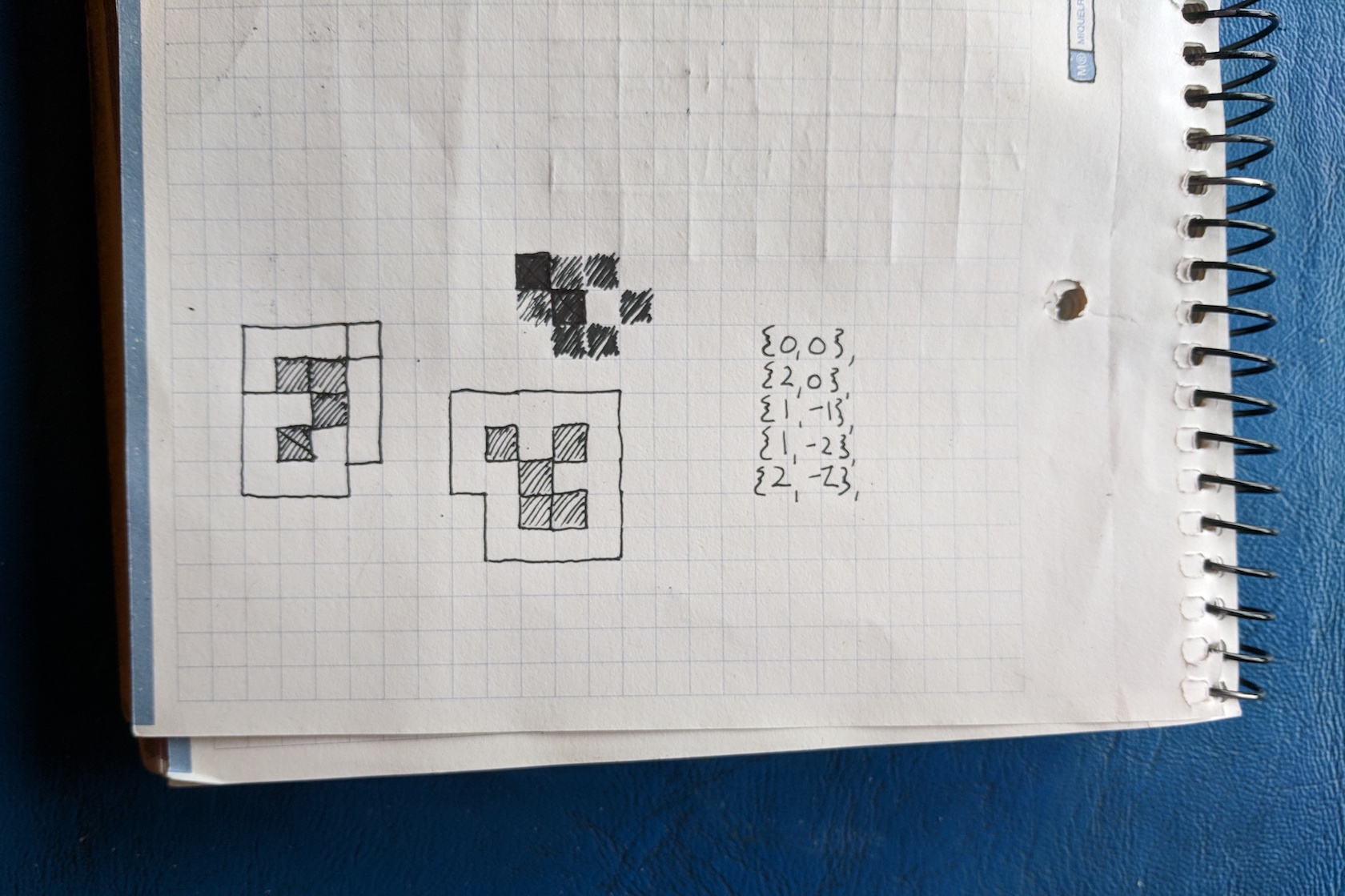

For the next round I teamed up with a programmer named Kenny. Things started similarly to the last round, except Kenny seemed to have a lot more experience. Rather than a 2D array of arbitrary size, he suggested recording “live” cells in a list of ordered pairs, the pairs representing their Cartesian coordinates on an unbounded grid. This turns out to be much more efficient than what Tim and I had devised earlier. The “universe” of cells has no borders (except for the memory limits of the machine) and so never needs to be explicitly resized. If a cell is living it exists in the list, otherwise it doesn’t. The main benefit is that it avoids keeping and managing unnecessary data. Still, Kenny and I got nowhere near completing the game.

Test: Am I expanding my coding horizons and learning how to do things differently?

Development: Research novel and more efficient ways of solving problems.

The constraint imposed upon the next session was that there was to be no talking. The real challenge, though, was that this time I was the one sitting in front of the keyboard, and with two professional programmers looking over my shoulder. Even though I’ve taken most of my classes in C++, and use it for most of my side projects, I still found it very difficult to type out even basic syntax in front of other people.

Test: Can I code in front of others?

Development: Pair programming, hackathons, etc.

The entire event assumed test-driven development, and the next session made it explicit. One person was to write the tests and the other person was to write code that made that particular test pass. One of the open source projects I’m contributing to right now involves writing tests for sorting algorithms, but this was the first time I’d written tests before anything else.

Here’s a quick summary of how to do test-first development that I wrote down in my notebook:

- Write the minimal test that can possibly fail.

- Write the minimal code that will make the test pass.

- Clean up code.

- Repeat.

Test: Is my code clean enough to test?

Development: Write tests before writing code.

I spent the two sessions working with a couple of software engineers from Intel. The constraints were mostly time-based. One involved setting a timer and handing over the keyboard every five minutes. In another, you had to write a test and the code to make it pass before the timer was up. If your test wasn’t passing before the time was up you had to delete everything that you’d added to the project.

Test: Am I writing code in logical chunks and with clear objectives?

Development: Formulate a goal, write a test, write code that passes the test.

By the end of the day my brain was spent, but I’d experienced a ton of teachable moments, thanks to the near-constant interaction with professional programmers. Perhaps the most important realization, though, was that today was a test, and that by my own measure, I’d failed.

I didn’t feel like a real contributor to most of the groups I was a part of and I didn’t feel like I’d shown what I’m really capable of. But that’s not a bad thing! This event was nothing more than a test that I could use to find out whether or not I’m improving as a programmer. It exposed a lot of “failing test cases” which I can focus on improving, so I went back through all of the sessions above and wrote out a test summarizing questions I should be asking myself and an idea for how I might develop that particular skill. And the best thing about this particular event is that it takes place every six months or so, so I’ll be back again to see how much I’ve improved.