Ever since Idara was born, I’ve sang her the same lullaby.

Why in the night sky are the lights hung?

Why is the earth moving ‘round the sun?

Floating in the vacuum with no purpose, not a one

Why in the night sky are the lights hung?

It’s a song by Fleet Foxes with a Simon and Garfunkel vibe. I love it, not only because Idara tolerates my singing of it, but because of the questions it asks and answers. The second verse:

Why is life made only for to end?

Why do I do all this waiting, then?

Why this frightened part of me that’s fated to pretend?

Why is life made only for to end?

I don’t think we’re programmed to live in the present or to appreciate what we have, but it helps to sing this song to Idara as I lay her down to sleep. It reminds me that someday all of this – the singing, the rocking, the childhood, the parenthood, everything – will end.

In October, the words that I’d grown so fond of took on a more dire meaning. Clyde, my mother’s father and my grandpa, was in the hospital. A few years ago he’d been diagnosed with and survived cancer. Now it appeared to be back, possibly for good. My mom said they were discussing hospice.

When I first heard the news, I wondered whether I should drive down to Albany to visit him that day or the next. But then he had surgery and it seemed like things might improve.

Still, it became harder and harder to sing that second verse to Idara. Sometimes I couldn’t sing it at all. It’s easy enough to think about death in the abstract, much harder when you can feel it approaching.

I visited Clyde several times in November and December and stayed up to date on his health via my mom. For a while it seemed like he might return to his former health, but then that idea faded away.

Toward the end of January he declined rapidly. It seemed that death was near. I found myself replaying all of my memories of him in my head.

The first one is a feeling. Not an emotion, but a real, physical feeling. A texture. I can feel it in my hands even as I write this. I bring them up from the keyboard, spread my fingers, and underneath I feel his balding head.

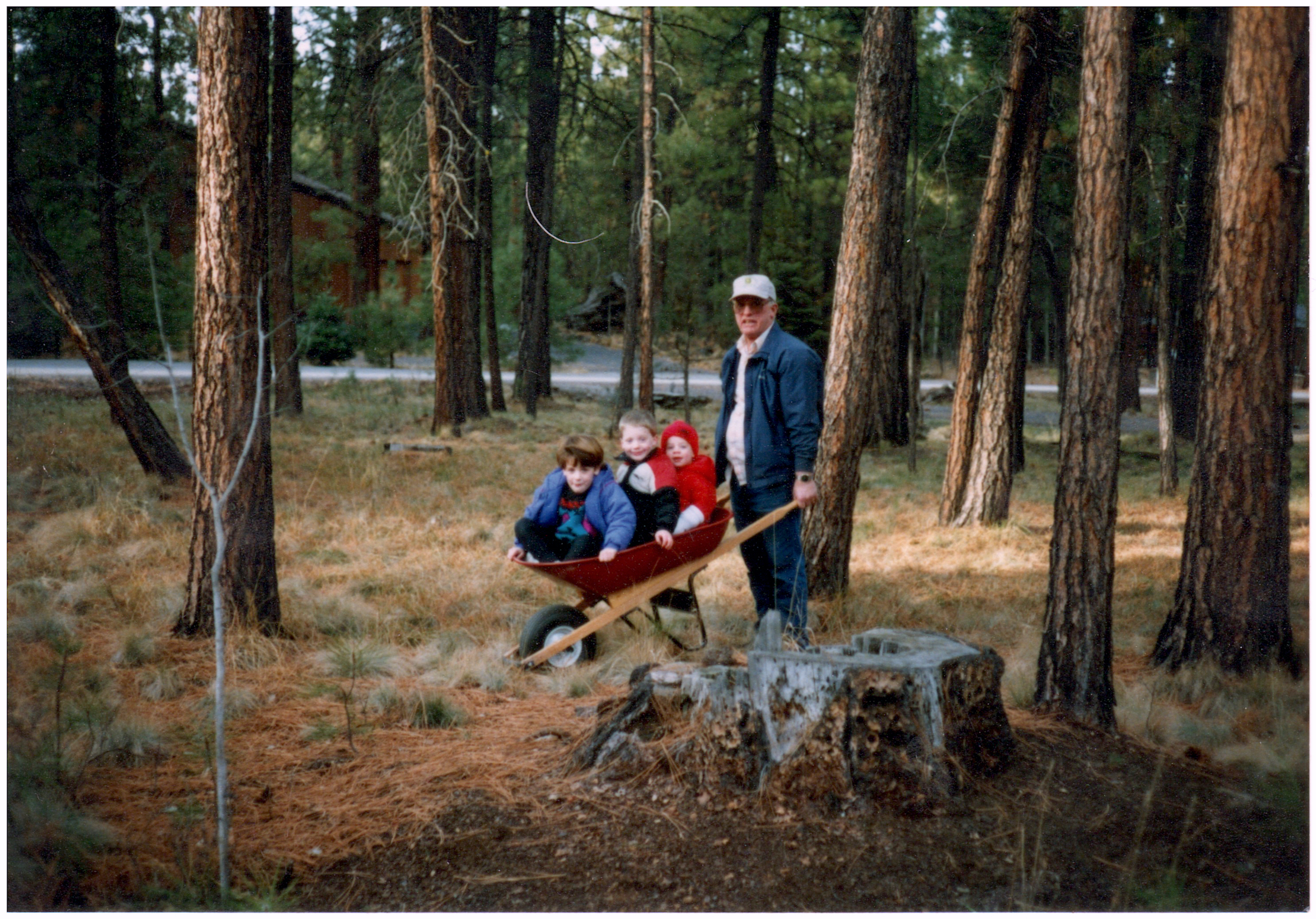

I used to ride on his shoulders. We’d walk through the trees, stepping on soft, pine needle-covered ground. I’d tire and lean forward, my hands resting on top of his head.

His were enormous, and his forearms, too. Like he’d been over-engineered, or stung by a hundred bees. When I grew up and we began shaking hands, his swallowed mine. I wondered if it was a lifetime of manual labor or if hands and arms just grow thicker with age, like tree trunks.

When I learned that even grammys and grandpas have names, and that his was Clyde, I wondered whether he was named for the horse, or if the horse was named for him. I never knew him to own horses, or ever saw him with horses, but surely they were around, somewhere. Clyde’s dales.

Grammy has a name, too. Claudette. Married forever, always together. They were so inseparable in my mind I thought the name Claudette must have been derived from Clyde, like woman from man. I wondered if when I grew up I’d have to find someone with a name like mine.

He always had a dog by his side. For a long time it was a yellow lab named J.D. John Deere? Jack Daniel’s? Just Dog? When I stayed at their house, which straddled two grass seed fields and an oak wood, J.D. and I would roam the fields and the trees in search of small adventures. He was always where he ought to be, doing what he ought to do. If there really is a magical bond between humans and dogs, Clyde and J.D. had it in spades.

I loved animals, too. When I was ten I read a pamphlet about vegetarianism and decided that I was going to stop eating meat. I announced my decision to Clyde one afternoon, to which he replied, “What about that cheeseburger?” Mom and I had stopped at McDonald’s on the way over and I’d ordered a Big Mac. “Well, this is the last one.”

Clyde could be scary. After a few hours driving around their property on his Gator, a small ATV, my brother Forrest and I discovered that we’d broken something in the undercarriage. Clyde didn’t suffer fools gladly, and I was terrified of how he’d react. Looking back, I can’t even remember if he reacted at all. Now I realize that this was really a testament to the respect I had for him, and how badly I wanted him to respect me, too.

As I grew up, I always wondered what Clyde thought about me and the choices I’d made. I’ve always been a city kid. Clyde, on the other hand, grew up in and around Tangent and became a farmer, and his arms carried the marks of a lifetime spent working outside. But I never felt a divide between us. When Rachael and I moved to Qatar in 2013, about as far from Tangent as you could get, no one was more interested in our lives there than Clyde. I even wrote a few blog posts based on his questions.

After Christmas, he got sicker and sicker, faster and faster. My brother Forrest and I had planned to visit him on a Sunday in January, but then on Friday night Forrest called and said that he thought we should go a day earlier. So we drove south on I-5, talking about music and trying to distract ourselves from the fact that this was probably the end.

Shortly after we arrived at the hospice house in Albany, Clyde died. It was Saturday, January 20th, 2018. A year ago today.

We went into his room a few minutes later. My mom and stepdad, brother and sister, two cousins and one cousin-in-law, and Grammy. Clyde’s body lay on a hospital bed in the middle of the room. I expected him to look like he’d just fallen asleep, but he didn’t. In fact, it barely looked like him at all. His mouth hung open and the shape and color of his face had changed. Now I understand why people describe death as the turning off of a light. His was gone.

Several weeks later we gathered again at a small pioneer cemetery west of Tangent. It sits in a stand of oak and fir trees. Clyde’s only son, Vern, was buried there. I was six years old. I remember telling my cousin how cool it would’ve been if Vern hadn’t actually died and came back out of the ground. “He’s gone,” she said. And now so was Clyde.

The service was small and simple. The pastor told a few stories about his life, but all I could think about were his ashes, stored in a small cardboard box on the table before us. When we walked to the grave site to bury them, I was struck by the size of the hole in the ground. To think that everything Clyde was, everything he did, everyone who he touched, to think that it all could be reduced to a small hole in the ground was almost unbelievable. Then again, I suppose there’s a poetry to it. We start from almost nothing, become something, and then return to where we began. Ashes to ashes.

The reception was held later in the day at a warehouse on one of the properties Clyde and Claudette used to farm. I didn’t know very many people there and didn’t feel much like talking, so I spent most of it wandering around outside. It was a beautiful setting. There were all of the farm buildings and equipment, of course, but everywhere else was bright green fields and further off in the distance, trees. Rain fell and the wind blew. And it was peaceful.