A couple weeks before Rachael and I were set to fly from Oregon back to Qatar, she asked me a question:

"I want to surprise you with something, but we'd have to drive for five hours into the middle of nowhere before you find out what the surprise is. What do you think?"

In retrospect, it sounds a bit like the setup for a horror movie. "Surprise! You're dead." But at the time I was just trying to think about what might be worth that five-hour drive. A hike? A rodeo? Transcendence?

A few days and one rented car later, we set out for the mystery destination, which Rachael directed me to, turn by turn. We drove for most of the afternoon, up over the Cascades and then down to the high desert, Madras, Prineville, and then up again into the Ochocos, past an abandoned pioneer cabin and signs warning us to watch for herds of sheep and cattle.

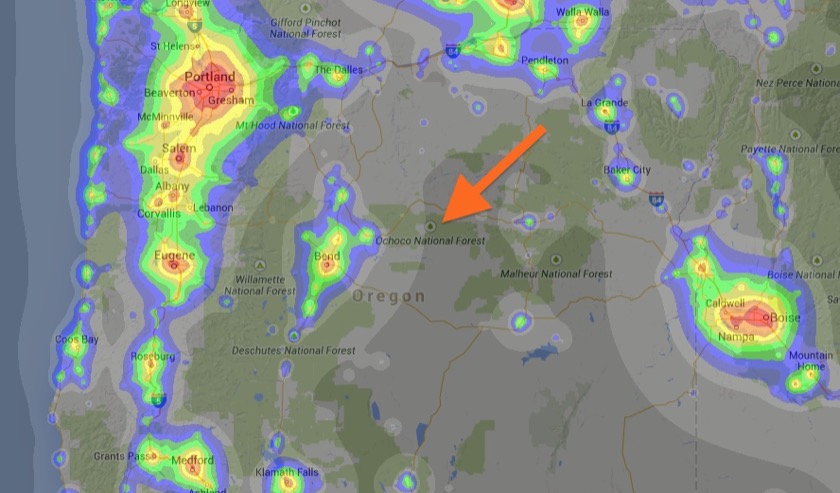

The further we got from civilization, the more I began to suspect that the point of this excursion had something to do with the stars. There were a few clues: First of all, Rachael knows I'm a bit of a space nerd. Second, the Ochoco National Forest has very little light pollution (see the map below), which makes for great stargazing. And third, the morning that we left Rachael's mom said that the clear weather "would be perfect for where you're going." Clear skies, high desert, can't lose.

As we got closer to our destination, I started to notice signs by the side of the road with the words "Oregon Star Party" pasted on. It looked like my suspicions were correct. So what's a star party? We were about to find out.

After a few miles driving over dusty gravel through a sparse forest, we came upon a grassy clearing on top of a small hill dotted with cars, campers, and tents. We pulled up to a homemade stop sign and a man in a tie-dyed shirt sitting in a camping chair holding a clipboard.

"Hi there! Are you here for the star party?"

"We are."

"Alright. How many telescopes did you bring?"

"None. Well, two." I pointed to each of my eyes, which elicited a groan from Rachael but no laughter from the man with the clipboard. He must've been too distracted by the fact that we'd come all the way out here without a single telescope, or maybe I'm just not funny.

"Go ahead on in, but don't forget to stop by the welcome tent to pay your entrance fee. You can set up your tent wherever you want."

We drove a lap around the clearing in search of a flat piece of dirt for our tent, but it was hard to focus on anything other than the degree of intensity with which our fellow Oregon Star Partiers had outfitted themselves. There were event tents and fifth-wheel trailers, custom-built camper vans and little campground motorcycles. And then there were the telescopes, hundreds of them, big and small, but mostly big, some so big you needed a ladder to look through.

We found a spot to pitch our tent off on our own at the edge of the clearing where we wouldn't be embarrassed by our lack of telescopic tools. Then we walked over to the welcome tent to pay our entrance fees, a steep $75 per person, and met a few of the organizers.

"Feel free to wander around and ask people what they're looking at. They'll want to show off their stuff. Just don't go down the road to the west where the astrophotographers have their equipment set up. They can be a bit, uhhh, grumpy. And did you bring a flashlight?"

"I have a headlamp."

"You'll need to cover that up with red tape so that it doesn't ruin anyone's night vision. And what about your car — will a light come on when you open the trunk?"

It was a good thing he was thinking about it, because I certainly hadn't.

"The glovebox, too. You can cover the lamps up with tape, or just pull the fuse that goes to all the car's lights."

Pull the fuse? These people were really, really serious about their night vision. And in a few hours, once I had a chance to look up at the unpolluted night sky with fully-widened irises, I would be too.

They were very friendly and eager to help us get settled once they found out that it was our first time (apparently most attendees are returners rather than newbies). They even signed us up for a "mentor" in the evening, a program which is designed to get children (and apparently children at heart) excited about astronomy. And while I didn't need much encouragement, I'm not sure I could say the same for Rachael.

The sun was low in the sky now, leaving only a little bit of time to wait before we'd be able to judge whether the destination was worth the trip. Rachael and I walked through the narrow thicket of trees bordering the grassy hill and found ourselves in another clearing, wholly separated from the campers and the telescopes and the people. It was just us, so we took a few pictures and watched the sun disappear behind the Cascades, giving way to what was to be the trip's headliner: a couple thousand stars, dozens of meteors, a few galaxies and planets, nebulae, and the list goes on.

As we were walking back through the trees and toward the party we spotted a bright light descending toward the northern horizon like a slow shooting star. It looked a lot like the International Space Station, which I've spotted many times with the help of emails from NASA and an app on my smartphone. There was no internet connection to verify the sighting, though, so I had to wait until we were back in cell range to check whether or not this was my first unplanned sighting of the ISS (it was).

Back on the other side of the trees we gathered in the middle of the clearing with a couple hundred other people to listen to a volunteer give an informative tour of the night sky with the help of a green laser pointer. I learned some fun facts, like that if the "seeing" is good enough one can spot our neighbor galaxy Andromeda with unaided eyes, and that the darker bands visible in our own Milky Way don't come from the absence of stars, but because galactic dust is blocking our view of them. Speaking of the Milky Way, as I photographed it below you're looking into its center, about 27,000 light-years away.

Next came our youth mentoring session, wherein a man whose face I only ever saw by dim starlight took us on a more detailed trip around the sky with the help of a small Dobsonian telescope. He showed us how to use it and then asked what we wanted to see, so we took a closer look at Andromeda and then spotted some double stars ("splitting," in astronomical lingo, because they appear to be one star with the naked eye but split in two (or four) upon closer inspection).

We also looked at a couple globular clusters, like the Great Globular Cluster in Herculues, which is home to about 300,000 stars. The man who was helping Rachael and me described it as a handful of diamonds thrown into the sky. It was one of the most spectacular things I've ever seen through a telescope.

Sometime around midnight Rachael and I walked back toward our tent, stopping along the way to ask permission to look through a telescope which was about ten feet long and two or three feet at the opening. I can't remember what we looked at, but I do remember that the man who shared his scope with us was very friendly and eager to share, just like the organizers promised.

At first, being a newcomer to the Oregon Star Party felt like being the only unrelated person at a family reunion. But once we had a chance to meet people we found everyone friendly and eager to make us feel welcome, even if it meant pulling themselves away from their eyepiece so that we could take a look.

Since we didn't have a telescope of our own to look through back at our tent, we laid our sleeping bags and pads across the roof of the car and stared up at the stars before we went to sleep. And while nothing compares to the gee-whiz effect of seeing a cluster or planet up close through a telescope, I still find staring up at the stars while laying on my back to be a much more moving experience. Not just because of the shooting stars or the sheer immensity of it all, but because I'm confident that humans have been doing this exact same thing for tens of thousands of years.

Having stayed up long past our bed times, Rachael and I awoke around 8 or 9 the next morning and found the star party abandoned, with just a few people milling around. The telescopes had been covered in some sort of special fabric for protection against the baking sun, and we were back in the car, headed back to Portland to make a complete circle of one of the best surprises I've ever been treated to.